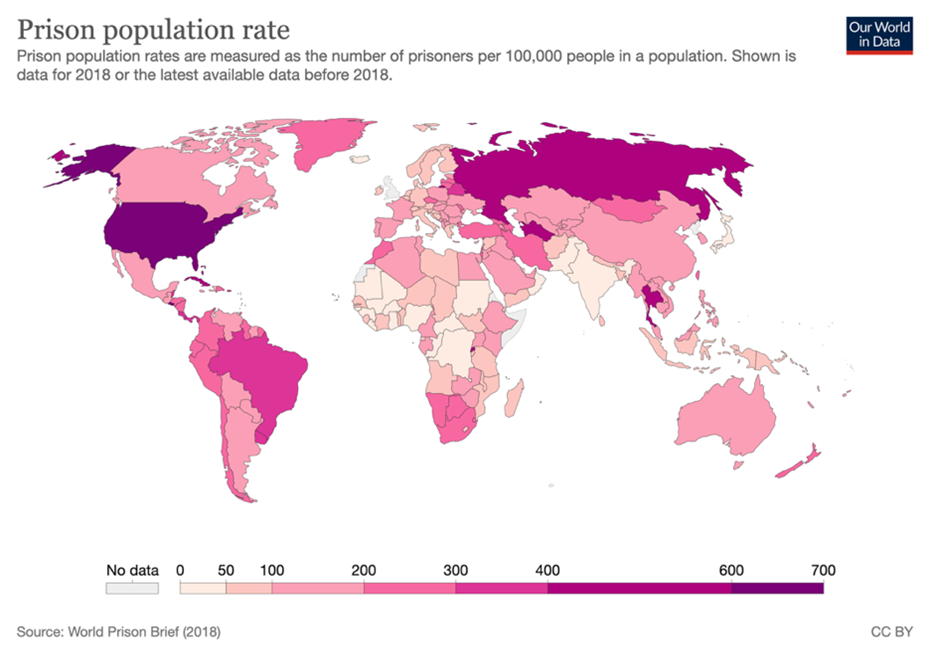

The United States has the highest prison population rate in the world with 655 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants – nearly six times more than China – and is home to a quarter of the world’s convicts. Might the land of the free also be the land of freedom deprivation? Undoubtedly, but it is also the land of business opportunity, where half of inmates work in prison, sometimes for the private sector. A business that generates several billion dollars in profit each year…

The virtues of penal labour, from Tocqueville to today

In the 1830s, the French government asked Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont to report on the American penitentiary system. According to them, the ideal model was one that reconciled the principle of moral reformation of prisoners with cost savings. In their eyes, the American system balanced these two imperatives by engaging inmates in labour, thereby reducing costs on the one hand and avoiding idleness, the mother of all vices, on the other. In a letter addressed to his father in 1831, Tocqueville wrote: “The American system is more economical than ours.” Today still, many American personalities – most often with close ties to the Republican party – advocate using inmate labour. One such proponent, Heather Mac Donald, explains that having a system in which prisoners work reduces part of the cost of incarceration (80 billion dollars in 2019).

The prison system, just another market?

However, the argument is a little misleading, as the majority of revenue generated by inmate labour in public correctional facilities is used to fund government services unrelated to the judicial or penitentiary system. For example, convicts were used as labour to clean up after Hurricane Katrina or as firefighters supporting the official fire crews during wildfire episodes. The majority of inmates work in prison if they are medically fit to do so and are not considered too dangerous. Most of them work on collective tasks that directly serve the prison in which they are incarcerated (this is called a ‘prison work assignment’ or an ‘inmate work assignment’). But approximately 7% of all inmates work in so-called ‘prison industry programs’, via UNICOR, for example, an organisation under the remit of the U.S. Department of Justice which places federal prisoners at the disposal of private companies. Many multinationals benefit from this arrangement, including McDonald’s, Walmart, Victoria’s Secret, and Starbucks.

“I cannot go on strike, nor can I unionize. I am not covered by workers’ compensation of the Fair Labor Standards Act. I agree to work late-night and weekend shifts. I do just what I am told, no matter what it is. I am hired and fired at will, and I am not even paid minimum wage: I earn one dollar a month. I cannot even voice grievances or complaints, except at the risk of incurring arbitrary discipline or some covert retaliation. You need not worry about NAFTA or your jobs going to Mexico and other Third-World countries. I will have at least five percent of your jobs by the end of this decade.

I am called prison labor. I am The New American Worker.”

Statement by Michael Lamar Powell, a prisoner in Capshaw, Alabama.

America is unique in that the management of its correctional facilities is either entrusted to public entities or outsourced to private companies. While this dual approach to prison management is old, there has been a sharp rise in the privatisation of penitentiaries since the Reagan administration. Private facilities may only hold 8.5% of incarcerated individuals, but their growth is far superior to public facilities, particularly those that are state-run.

Today, two large corporations, the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) and the GEO Group, share this huge market. In 2012, for example, the CCA offered to purchase the hitherto government-run correctional facilities of 48 states. Over 20 years, the CCA’s turnover has increased by 500%. What is the appeal for these private corporations? The answer is simple: the prisons are a golden goose paying an average hourly wage of less than a dollar. In some southern states, in Alabama or Texas, the work of inmates is not remunerated at all. In these conditions, it is easy to understand why these companies contractually agree on a guaranteed average minimum occupation rate of 80 to 100% and are very active in lobbying for prison sentences, a practice that is questionable from an ethical point of view. When crime rates decline, public state-run prisons can end up under capacity because prisoners are sent to private prisons as a priority. Have prisons become just another production site? What explains these practices that seem to fly in the face of American ideals imbued with the philosophy of the Enlightenment?

Prison in the United States, a reflection of the country’s political philosophy and of American history

To understand how the prison system works, a look back at the origins of American democracy is necessary. James Whitman, a law professor at Yale, posits that the democratisation process took place very differently in Europe than it did in the United States. According to him, European societies democratised by “levelling up”, or in other words by extending to all the right to expect the level of treatment once reserved for those on the highest rung of the social hierarchy. Put differently, in Europe, where once there were aristocrats, “we are all aristocrats now”. In his view, the United States did the opposite: “American egalitarianism, by contrast, is, I suggest, an egalitarianism of leveling down, which proclaims, in effect, that there are no more aristocrats – that we all stand together on the lowest rung of the social ladder.” This would explain why European law considers that prisoners are deprived of freedom, but not of equality and fraternity, whereas American prisoners are treated without any regard. In certain respects, they are treated as people were in the Ancien Régime. Whitman sees in this the origin of American justice’s harsh treatment of prisoners and does not hesitate to consider prison a place where individuals are deliberately degraded. The working conditions they are compelled to endure, the low pay, and the lack of social rights are merely the concrete expression of this. This is in striking contrast with Germany, for example, where prisoners who work enjoy social rights and paid leave.

But there is another factor that explains both the high levels of incarceration and the almost systematic practice of forced labour, one that relates to the conditions under which the United States ended slavery. The 13th Amendment of the United States Constitution, which proclaimed its abolition in 1865, states that slavery or involuntary servitude is justified as punishment for crimes committed:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States…

In other words, the amendment that officially abolishes the practice of slavery allows for an exception… This, in part, explains the way prisoners are treated and the fact that they are not considered “employees” or “workers” under the common law definition of employment…

Moreover, the abolition of slavery has had another indirect impact by depriving the southern states (including Alabama and Mississippi) of a four million-strong labour pool. According to the academic Melissa Rubio, the justice system then took over by providing a work force in the form of convict labour. In the decades that followed, these same states adopted so-called Black Codes which allowed them to imprison Black people on the mere grounds of “vagrancy”, a charge that could be brought against anyone found guilty of theft, public intoxication, family neglect or professional negligence, or even someone whose conduct was deemed to be provocative or disorderly. In other words, as underlined by Melissa Rubio, it is no exaggeration to say that part of the Black American population went from plantations to prisons. With figures to support her claims, she estimates that the counties engaging in slavery prior to 1865 deliberately incarcerated more Black Americans than other counties, in order to have access to servile labour. The result? To this day, African Americans make up just 13% of the population of the United States, but they account for 40% of the prison population. In total, 1.5% of Black American citizens are in prison, versus 0.3% of white citizens…

To conclude, let us get back to Tocqueville, a keen observer of the American prison model, who had, in his day, identified the economic benefits and social costs of the system. While it is clear today that running penitentiaries can prove profitable for private operators, does it actually reduce delinquency and prevent reoffending? This is a complex subject that will be discussed in a later article.