In a few short years, the money and payments arena has seen some major changes: the simultaneous and in some cases competing development of new payment methods, the rise of cryptoassets and the emergence of private and/or central bank digital money. These new solutions pose numerous questions and will have fundamental macroeconomic, political and ecological impacts. First and foremost among these, they raise the issue of state sovereignty. Undeniably, money has a sovereign dimension and a very marked public service mission. Can it, and indeed should it, be allowed to move outside the sphere of control of states and central banks? What is the future of money?

Public digital money today

According to the ECB, “In this new era, a digital euro would guarantee that citizens in the euro area can maintain costless access to a simple, universally accepted, safe and trusted means of payment.” The first benefit highlighted would be the costless nature of this new payment method, in contrast with traditional tools (payment cards, etc.) which are coupled with insurance when they are sold. In theory, it appears credible, or at least possible, that a digital euro would be available free of charge, because households and businesses could hold accounts directly with the central bank, bypassing the account fees charged by traditional banks. However, the ECB also states that “a digital euro would not replace cash, but rather complement it.” Yet if the digital euro developed alongside the current euro rather than replacing it, traditional bank charges would continue to exist, so there would be no benefit on that level.

But is a parallel existence really feasible in the medium and long term? We could ask whether there is a hidden economic policy agenda to put an end to cash payments and thereby reach an ultimate goal practically unattainable by any other method: to make all payments traceable and stem the majority of frauds and illicit transfers, from under-the-counter arrangements and small-scale tax dodges to gains from illegal activities (drug trafficking, terrorist financing, etc.).

In addition, cash is relatively expensive to print, handle, circulate and transport, and it has an environmental footprint too.

The end of cash is however as yet taboo, because most people see holding it as their final freedom. The topic is particularly sensitive in Europe, especially for the Germans who, when they gave up the Deutschmark in favour of the euro, felt their identity shaken to the core. Germany’s deep-rooted attachment to its currency dates back to the era of Bismarck (1815-1898), a time generally accepted as marking the origins of the power of Germany, which was then dominated by Prussia. One feature of Bismarck’s union with Austria was that alongside the common currency that was created, the various local currencies continued to exist.

Even today, Germans are strong believers in cash as a symbol of freedom. The French, who invented chip-and-pin, are also strongly attached to bank cards and to withdrawing money from ATMs at a dense network of branches.

In contrast, the Nordic countries, known for their “flexicurity” welfare state models based on mutual trust between governments and citizens, and for ranking among the top countries in the world in well-being surveys, also seem to be leading the way in adopting decentralised financial payments technologies. For example, Swedes showed their usual enthusiasm for tech innovation when, in record time, they began en masse to use an application named Swish to transfer money from one account to another in real time, with no commission fee. But did Sweden jump the gun? As cash began to disappear, people started to worry and the authorities found themselves having to pass a law to oblige banks to “provide a sufficient level of cash services”.

Outside Europe, the leaders of the digital technology race are already several steps ahead. China, for example, aims to be the first major country to issue a sovereign digital currency, the e-yuan. Large-scale tests have begun in the country, where mobile payments are already popular. In December, 10,000 stores in Suzhou offered their customers the option of paying in e-yuan.

According to the Bank for International Settlements, 80% of central banks are considering launching a digital currency, and 10% have a project in the pilot phase.

Be that as it may, should we believe that “a world without cash is the prelude to a totalitarian society, hidden behind a screen of modernism”? Should we be concerned? What would happen in the event of a system-wide IT breakdown or a cyberattack? In our opinion, the visceral fear of losing our freedom or having our every move tracked is the product of an overactive imagination. Indeed, our transactions are already closely monitored and our data collected, by the tech giants in particular.

Therefore, wouldn’t we be better off having our payment data collected by an independent public body like a central bank? One study by the CNIL (French data protection agency), among many others, showed that data management algorithms like those used by the tech giants do not in fact bring groups of people together through social media, nor do they increase transparency. They actually tend to act as echo chambers, reinforcing our beliefs and amplifying silos to the detriment of open, universal relationships.

Establishing strong public digital money is vital for monetary stability

The IMF estimates that the total value of the cryptoassets in circulation worldwide ballooned tenfold in a year, to stand at more than $2,000bn in September 2021.

Bitcoin, which is extremely volatile, was the subject of intense speculation during the Covid lockdowns. Its value quadrupled during 2020 to hit $40,000 in January 2021. It then continued to rise, reaching a figure in excess of $60,000 by mid-year.

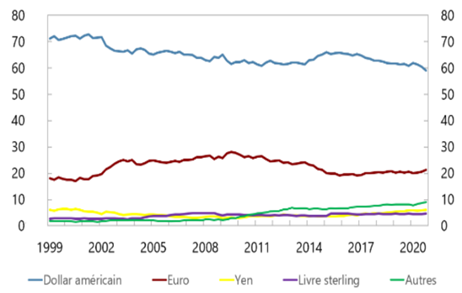

Traditional currencies are facing increasing competition from private digital currencies, including to their status as the dominant reserve currency, as this graph shows. In the fourth quarter of 2020, the US dollar’s share in global foreign exchange reserves reached its lowest level in 25 years (IMF, May 2021).

The euro is also struggling, faced with the emerging Chinese yuan and the return to favour of gold, which is seen as a hedge against the current reflationary context.

Gold and bitcoin appear to be increasingly complementary. Both provide the desired protection against inflation, but they have differentiated and opposite diversification effects. For example, the SPDR Gold Shares (GLD) and the iShares Gold Trust (IAU) – the main ETFs for gold – saw high outflows in December 2020, whereas the Grayscale Bitcoin Trust (GBTC) saw unprecedented inflows.

Private digital currencies (stablecoin-type products that fluctuate less dramatically than other cryptocurrencies) such as Meta’s Diem could emerge as reserve currencies, according to another document from the IMF.

The IMF’s report examines shifts in the international monetary system and the factors that could influence the role of the US dollar as the dominant reserve currency, including new payment systems and digital currencies.

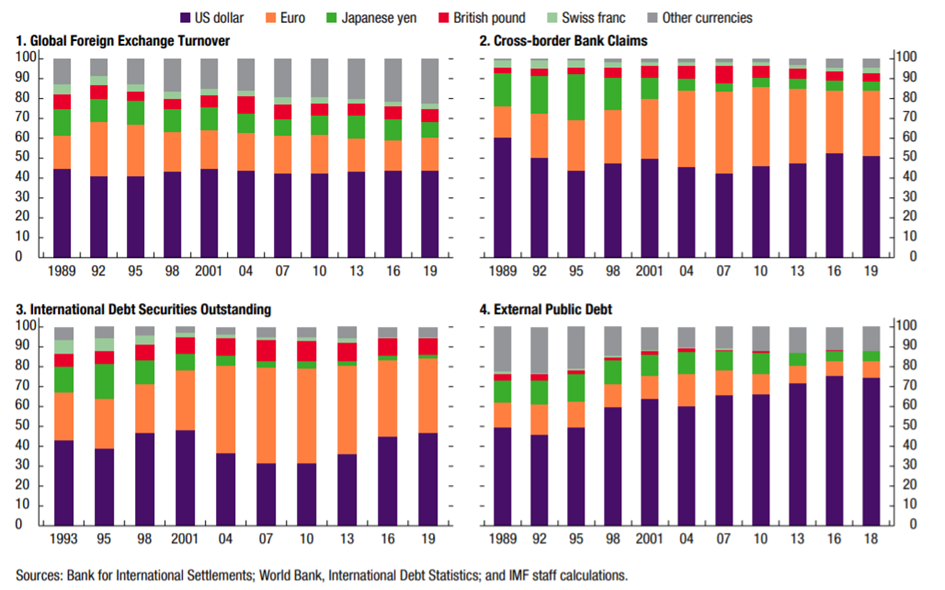

The financial links created by the currencies used to denominate external debt and cross-border interbank claims have become an increasingly important driver of reserve currency configurations since the global financial crisis, in particular for emerging markets and developing economies.

These financial links are illustrated and summarised in the tables below:

Composition of currencies in international currency exchanges and main sources of international claims.

In short, we cannot assume that the traditional currencies of the financial and monetary powers will be in a position to maintain their dominant status without competition from digital currencies.

Could public digital money be a lever for returning power to central banks?

Central bankers can also see digital money as having potential to help them avoid the pitfalls they normally face when implementing monetary policy in the economy. The enormous advantage of digital money would be that economic actors could hold accounts with the central bank directly. This would offer the advantages generally attributed to helicopter money, because it could:

- Circumvent any blockages in bank credit channels,

- Bypass the interbank markets and avoid disrupting bank interest rates,

- Place fresh money straight into the hands of individuals (thereby increasing wealth more directly and spreading it more effectively)

- Inject money without requiring asset purchases, which boost asset prices and benefit solely the holders of those assets, thereby increasing inequality,

- Mop up the excess reserves currently present in the banking system (when banks receive more liquidities from the central bank via asset purchases than they can actually use).

In a nutshell, public digital money would make it far easier to implement monetary policy, avoiding the harmful side effects generated when asset purchases or liquidity injections transit via the banking system, as is the case today. An excess liquidity scenario, such as we are currently seeing, is typically a tricky situation which can make it difficult for a central bank to achieve its objectives (monetary policy stalemate, liquidity trap, etc.). Digital public money could give central banks back a degree of control and dominance in their relationships with other financial institutions and provide them with a more direct way of adjusting the money supply (in Europe at least, the money circulating in the economy originates almost exclusively from credit operations by these financial institutions).

Is public digital money a way to counter the perceived threat from bitcoin?

The temptation to develop state-backed digital money such as the euro or the yuan is also a function of the weaknesses and dangers inherent in private digital currencies.

To understand some of these issues and weaknesses, we simply need to realise that more than 13,000 private digital currencies coexist today. Inevitably, this leads to market inefficiencies with gaping opportunities for arbitrage through which certain funds specialising in cryptocurrency are able to exploit price differentials to achieve profitability levels of 100%.

Moreover, bitcoin is not really a currency as such: confidence in a currency normally derives from confidence in the issuing institution, and in the assets and liabilities on its balance sheet. Theoretically, the independence of the issuer (a central bank) increases confidence in the currency issued. Bitcoin does not have this backing and no one is obliged to accept a payment denominated in it. (In point of fact, France’s Money and Finance Code actually prohibits bitcoin payments.)

But despite these genuine weaknesses, it is estimated that the market for cryptocurrencies is continuing to grow, recently exceeding $3,000bn (of which 42% relates to Bitcoin alone and 20% to Ethereum).

Interestingly, there is a clear correlation between the development of sovereign digital money and sudden halts in the development of bitcoin and other private currencies. China, where the central bank’s “crypto yuan” project has already reached an advanced stage, has now declared that “all transactions linked to cryptocurrencies are illegal. Beijing has forbidden all financial institutions, payment companies and internet platforms to authorise trade in cryptocurrencies.” This is a regulatory attempt to reduce the influence of bitcoin in the country. Indeed, in 2017 it was estimated that two-thirds of bitcoin mining took place in China.

The advantage of a central-bank-controlled digital yuan is obvious: using a centrally managed digital currency gives the authorities more control and reduces the risks of tax evasion, capital flight, crashes, etc.

Lastly, let us turn to an issue linked to the very survival of our planet: currencies that have to be mined before a financial transaction can take place use a disproportionate amount of energy because of the processing power of the servers involved. Here is a staggering example: in 2021, bitcoin consumed 143 TWh of energy, more than the total used by the Netherlands (111 TWh), and almost as much as the United Arab Emirates (120 TWh) or Norway (124 TWh). “As competition has increased, bitcoin mining has become an industry in its own right, requiring specialised equipment, servers and enormous data centres with sufficient cooling capacity to prevent the computers from overheating.” Citizen Side.

So it is clear that a thorough cost-benefit analysis is vital. As Cesaria Beccaria reminded us, “in political arithmetic, it is necessary to substitute a calculation of probabilities, to mathematical exactness.” This analysis needs to be wide in scope, encompassing the challenges relating to geopolitics, the climate, the effective implementation of monetary policy and the drawbacks of “private” digital money, which is currently being given free reign to develop in Europe.

Ultimately, the issue at stake is how assertive governments should be in the face of private companies. This is a question we need to answer before private currencies reach a dominant position and dispossess governments of a sovereign function that exists for the common good.