To cope with the high influx of patients, European hospitals called for additional intensive care beds. What if this shortage, in this time of pandemic, was the consequence not of a lack of resources but rather of a dilemma caused by resource allocation that places efficiency ahead of resilience? This debate is very familiar to economists and can apply to many spheres.

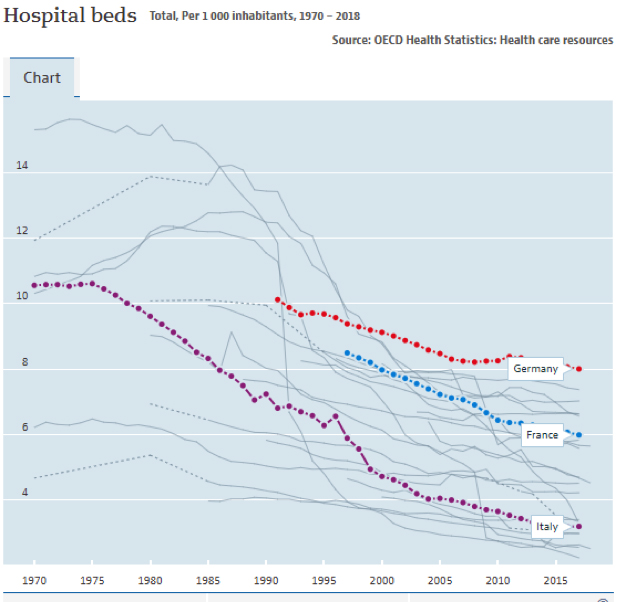

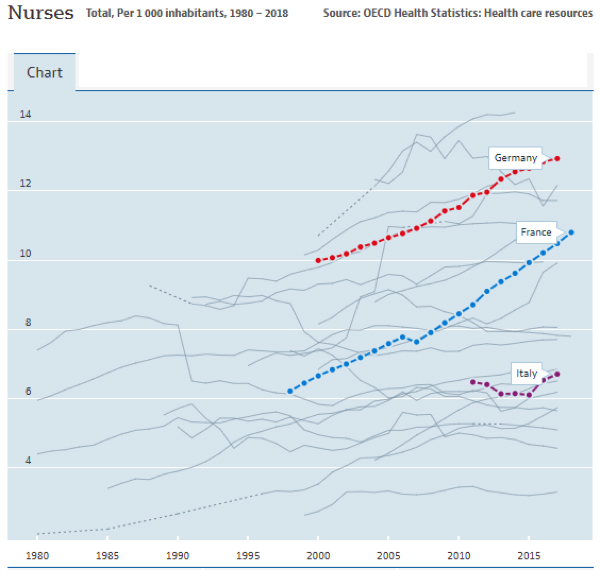

In OECD countries, statistics show that the number of hospital beds per capita has been decreasing regularly for 30 years. This can be explained by advances in medicine that reduce the length of hospital stays. Some patient care has also been moved to other medical facilities. Plus decision-makers have no doubt been influenced by Roemer’s Law, the corollary of Parkinson’s Law, which states that a hospital bed built is a hospital bed filled, since ─ to some extent ─ supply creates its own demand. But contrary to a popular misconception, the decline in hospital resources is not across the board. Relative to the number of inhabitants, the number of nurses and, more broadly, medical expenditure have increased.

Under normal circumstances hospitals are not under capacity, since the bed occupancy rate is around 75% in OECD countries. Nevertheless, the coronavirus epidemic has cruelly highlighted the lack of available beds in intensive care. This shortage during the epidemic should not surprise us. Since hospitals are regularly asked by the government to rein in their budget, it is impossible for them to operate permanently at overcapacity just in case…

This sacrificing of resilience in favour of efficiency is a classic phenomenon also found in mass-market retail. When the epidemic broke out, the British were accused of panic buying basic necessities. The reality is that 90% of consumers limited themselves to buying a bit more a little more often. For the sake of efficiency, supermarkets avoid storing goods locally. This keeps the commercial space they occupy to a minimum. Using “just-in-time” keeps costs down under normal circumstances, but this approach proves to be incapable of handling a demand shock in a time of crisis.

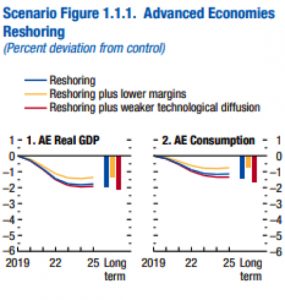

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, some rich countries are talking of encouraging the “reshoring” of certain activities, i.e. moving them back to within their borders. But the cost of this is considerable. The IMF estimates that reshoring some production to replace 10% of imports would, overall, lead to a 2% drop in household consumption.

All these examples show that efficiency and resilience are two goals that are difficult to reconcile. The economist Milton Friedman summed up the constant presence of difficult trade-offs that society must make by stating that “There is no such thing as a free lunch”. Everything has a cost, even if it is hidden. This raises the following question: are we willing to pay more for more resilient hospitals, supermarkets and value chains?