It was 45 years ago, but it seems like yesterday: in 1976, the horror film Carrie told the story of a young girl exhibiting supernatural powers which her mother associated with the start of menstruation. This story has its roots in ancient beliefs linking menstrual cycles, lunar cycles and magic. It is also a reminder of the extent to which, even today, menstrual bleeding can be taboo, synonymous with impurity, awkwardness, scorn, or even exclusion. Does this “universality of terror”, in the words of Albert Samuel, explain why human societies have done very little to address this issue which concerns half of humanity?

Menstrual periods – a taboo representation, between beliefs and obscurantism

Numerous religious texts raise the topic of menstruation. In these, women are described as impure, capable of infecting those who approach them. The book of Leviticus says: “When a woman has her regular flow of blood, the impurity of her monthly period will last seven days, and anyone who touches her will be unclean till evening.”The image of a woman soiled by her menstrual bleeding is also found in the third monotheistic religion, Islam. Menstruating women are not allowed to perform the five daily prayers and they are not permitted near the Kaaba, a sacred site.

Outside of the religions of the Book, wariness of menstrual periods is practically universal. Once suspected of having evil powers during their period, women are still excluded from social life in many places: in Nepal, for example, the Chaupadi tradition forces them to live in isolated and unsanitary huts. In Mongolia, being in contact with menstrual periods is a “quasi-omen of death, […] extremely defiling: this is the reason why the sacred mountains are forbidden to women ”.

As a result of this taboo, dealing with one’s menstrual flow remained a strictly private affair for centuries. What we call sanitary products, period products or menstrual hygiene products nowadays only became commonplace consumer items in the second half of the 20th century, several decades after the automobile… It is not unreasonable to view the evolution of the female condition through this prism. In short, another way to write the history of women…

The long history of menstrual hygiene products

The first traces of menstrual hygiene products date back to nearly 2000 BCE, with the first forms of tampons invented in ancient Babylonia. In Egypt, aristocratic women used bits of wood wrapped with fabric. However, religious beliefs curbed this practice, associating it with loss of virginity. During the Middle Ages and the early modern period, women did not wear underwear. They let the menstrual blood flow and it was very often absorbed by their petticoats.

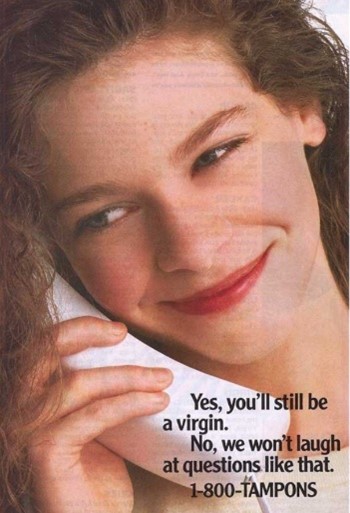

It was not until the 20th century that new ways were sought to improve the comfort of women during their menstrual periods. The Great War marked a major turning point. In 1920, aware of the potential market, the company Kimberly-Clark developed the first washable sanitary pads. The advertising campaigns launched for the occasion got people speaking more freely about this still delicate topic. Fifteen years later, the brand Tampax launched its first eponymous product. Although an undeniable step forward, for a long time it was only accessible to the elite of society and to married women. Indeed, it was accused of compromising virginity, a belief that persists to this day.

In addition, a combination of misogyny and racism also put the brakes on a potentially major innovation for improving the comfort of women. Mary Kenner is a striking example of this. Mary had invented a belt for disposable sanitary pads. Although interested initially, manufacturers in the sector pulled out of the project once they realised that “M. Kenner” was a woman, and a black one at that! Generally speaking, for a long time the prevailing lack of gender diversity in the professional world, and notably in advertising, kept women’s issues confined to a male perspective and discourse.

Menstrual hygiene products revealing inequalities

These days, the use of menstrual hygiene products has become widespread, in the West at least. And yet, this undeniable progress reveals social, cultural and financial inequalities.

The composition of menstrual hygiene products has been the subject of controversy over the last few years. In 2017, a study by the French DGCCRF (the General Directorate for Competition Policy, Consumer Affairs and Fraud Control) revealed the presence of dangerous chemicals in various types of menstrual protection. The matter was raised with ANSES (the French National Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety) which, in a 2019 report, responded: “To date, external menstrual hygiene products (pads, panty liners) have never been associated with menstrual toxic shock syndrome.On the other hand, cases have been reported in connection with the improper use of tampons or menstrual cups, notably due to prolonged wearing or to the use of internal protection unsuited to the menstrual flow (too high a level of absorption or too large).”INSERM (the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research) confirms that toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is linked to an improper use of said menstrual hygiene products.

On a different note, period poverty remains a reality for millions of women who struggle to afford sanitary products. In France, this figure is estimated at two million, enough to warrant public health policies. This year, President Macron announced the allocation of five million euros to the development of period product access schemes. Local stakeholders are also tackling the issue. This is the case of the University of Lille, for example, which is now making free sanitary products available to its students.

The Scottish example is even more striking: sanitary products have been free in all educational establishments since 2018 and in November 2020 the Scottish Parliament extended the free provision of period products to all women, to the great delight of Prime Minister Nicola Sturgeon. A similar system is in place in Uganda, where the government has provided young girls with quality sanitary products for two years, a move which has increased their attendance at school by 17%. It is clear that, in the absence of proactive policies, the consequences on the most vulnerable female populations can be considerable, which reinforces gender inequalities.

While the free provision of menstrual hygiene products is not yet generalised, the matter of their taxation has become a key issue in terms of gender equality. Indeed, considering that the use of these products is not a consumption choice but rather a necessity, imposing a tax on them is tantamount to taxing the female condition. However, some progress has been made: countries such as Kenya, Australia, Ireland and Canada have completely eliminated the so-called “tampon tax”. France, Great Britain and Colombia apply a reduced tax rate of 5%. Germany, Argentina, Sweden and Denmark, on the other hand, apply taxation levels similar to those of wine or tobacco…

Finally, the latest topic to spark debate is the question of menstrual leave. Last April, a survey conducted by the French market research and polling firm Ifop for Eve and Co showed that 68% of the employed women surveyed were favorable to the introduction of menstrual leave. The survey relayed the initiative of a Montpellier-based company that had just introduced this type of employer-paid leave. Menstrual leave is already in place in Japan and Indonesia, however in France it is far from gaining unanimous approval, with some people seeing it as another form of discrimination and others as a major social advance…