Populism is a complex ideology that first appeared in Russia in the late 19th century. At the time, it was a movement started within the progressist, democratic and demophilic intelligentsia, which advocated genuine concern for the populace with the aim of helping and educating them, but also of maintaining contact between the social elite and the common people. Since then, the nature of populism has changed and there is a strong possibility that the political actions of its representatives, carried out on behalf of the people, are now turning against the latter and risk pushing them further into poverty.

While originally intended as a means to connect the top and bottom of the social pyramid, populism can now be defined as a simplistic ideology pitting the “good people” against the “corrupt elite”. The leaders of populist parties often come from this elite, claiming to have turned their back on it to defend the interests of the “little people”, who have been scorned by a dominant minority for too long. Among other things, they promise to accelerate growth and redistribution while ignoring all orthodoxy. This type of discourse gains circumstantial legitimacy when it is delivered within a gloomy context combining economic stagnation, deep socio-economic inequalities, and cases of corruption. Latin America is a textbook case and its history underscores an essential fact: populist policies are expansionary policies that result in more poverty.

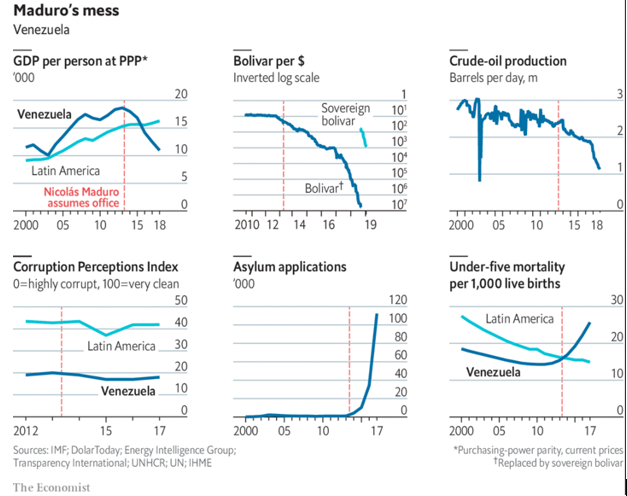

In 1991, the economists Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards published a book entitled The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America. In it, they demonstrate that populist leaders immediately cater to the expectations of their voters by introducing expansionary policies, meaning policies involving fiscal or monetary stimulus measures. Granted, these result in strong economic growth and greater redistribution. However, Dornbush and Edwards underline that this situation generally does not last: deficits worsen rapidly and are monetised, accelerating inflation, the foreign currencies needed to import goods become scarce and economic productivity plummets. The end result is an economic crisis that penalises the entire population and particularly the poorest. Today, this analysis explains, for example, the dramatic crisis hitting post-Chavez Venezuela, where the poverty rate is over 80% while the country is experiencing unprecedented emigration.

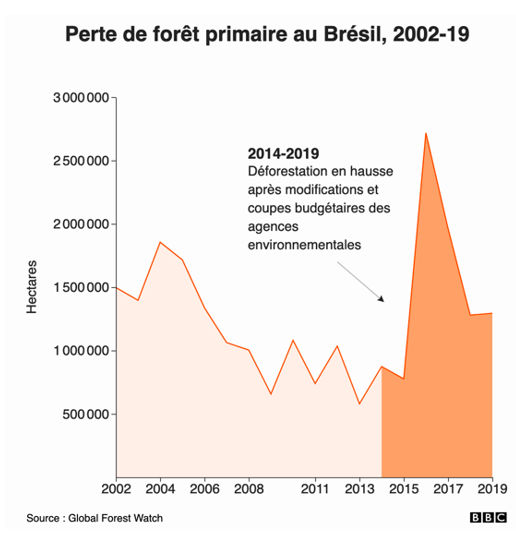

Let us consider another Latin American country, Brazil, currently governed by the right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro. He is engaged in another type of impoverishing expansionary policy: the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest.

In the short term, burning the forest provides more land for soya cultivation, cattle raising or mining activities. In the longer term, deforestation is taking the Amazon to a point of no return where its homeostasis will be broken, leading to its disappearance. This would have very expensive consequences for Brazil in particular, as its agriculture is largely dependent on the rainfall generated by the Amazon rainforest. The rest of the world would suffer from the loss of the ecological services provided by the Amazon in the form of carbon storage or biodiversity conservation. This explains why President Bolsonaro’s environmental policies are strongly criticised by environmentally-aware representatives of the international community, especially in Europe.

Certainly, Europeans are right to be alarmed at foreign economic policies that threaten to throw the planet out of balance. Nevertheless, the actions of the European Union itself are not beyond reproach. Indeed, at each European election, numerous members of far-right populist parties are elected as members of the European Parliament. These members tend to oppose any European environmental policy with the same arguments as those put forward in Brazil: environmental protection is a tax on businesses; it would be expensive, unfair and ineffective. Thus, populist programmes built around impoverishing expansionary policies can also be found in Europe.

Generally speaking, populists engage in unreasonable extraction of the resources that surround them, without ensuring their renewal. Once their policies are in effect, the consequences can be irreversible and international. But we must remember that when certain strata of society genuinely feel abandoned, the lure of the “extremes” is amplified. The recent rise in populism around the globe suggests that addressing this feeling must be a priority. Preventing the dislocation of societies can be far less costly than attempting to piece back together the economy and the environment. To conclude and to take a more measured look at the political phenomenon that is populism, perhaps it should be seen as a wake-up call and the signal that democracies may have neglected a segment of the very people they were supposed to represent and protect. From this viewpoint, our democratic regimes have some work to do and a discourse to reinvent in order to return to the earliest form of populism, which was driven by a desire to close the gap between the social classes. After all, was not their entire aim, in the words of Abraham Lincoln, a “government of the people, by the people, for the people”?