It is not unusual to read that private players threaten state prerogatives. A detailed analysis of the situation, including through the prism of international investment agreements, gives this idea a certain credibility while shedding some new light on it. Indeed, the state has the means to retain the monopoly of public power.

Public power is “the administrative translation of the political reality that is power”. Thus, in the interest of the greater good, the state may take coercive actions to ensure the safety of its citizens. The lockdown measures imposed in France in the first quarter of 2020 to slow down the SARS-Cov-2 epidemic is a recent and spectacular illustration of this. Beyond the oversight of the constitutional council, public power is governed by administrative law and penal law via two jurisdictions. In France, the first is the Conseil d’État (Council of State). It is the supreme administrative judge that guarantees the lawfulness of public action and ensures the civil rights and liberties of citizens are protected. The second, the Cour de Justice de la République (Law Court of the Republic), was established to try members of the French government for acts performed in the holding of their office and classified as serious crimes or other major offences at the time they were committed (article 68 of the French Constitution). These two jurisdictions are very busy right now, because many citizens consider that the measures taken by the government to tackle the epidemic do not sufficiently protect public health and, in some cases, even lead to involuntary manslaughter.

These legal proceedings brought against public power occur within every state. But some people, particularly in the United States, would like to give the rule of law more international reach. During the COVID-19 epidemic, lawsuits have been filed to seek compensation for the damages caused by the epidemic in the United States. These lawsuits have very little chance of success because, in accordance with the principle of jurisdictional immunity of foreign states that applies in France and in the United States, the courts of one State have no jurisdiction over another State when “the foreign State is sued for acts accomplished by it in the exercise of its sovereign rights”. This may be regrettable, but lifting this international immunity would without doubt create additional geopolitical tensions in a context of strained trade relations between China and the USA. Were legal proceedings to be brought against China in the United States, there would be a high risk of retaliation from Beijing and from all the countries severely destabilised by America’s geopolitical actions. Somewhat ironically, the “hard power” of great military powers is wielded thanks to the free rein provided by the principle of jurisdictional immunity which, as underlined by the European Court of Human Rights, aims “to promote comity and good relations among States by respecting each State’s sovereignty.”

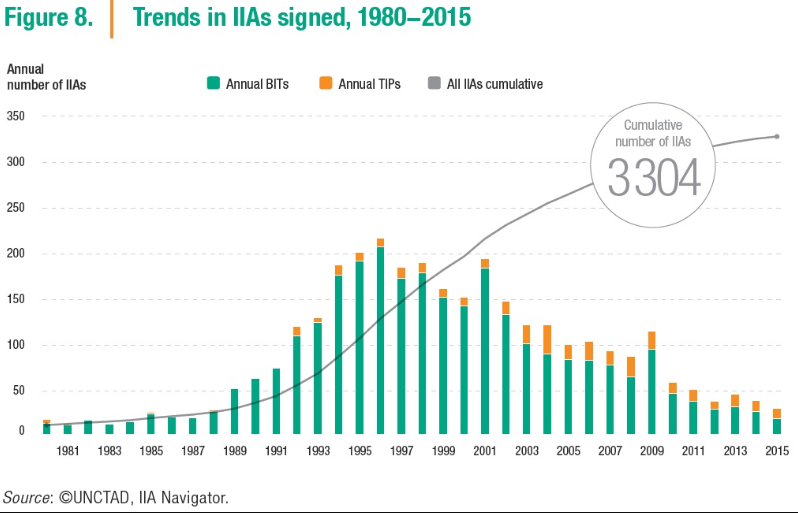

Ergo, the sovereignty of states is a principle constantly reaffirmed in legislation. Nonetheless, certain states have agreed to give up part of their sovereignty to achieve certain economic development goals. To promote and protect the direct international investments made my multinational companies, many countries have signed international investment agreements (IIA).

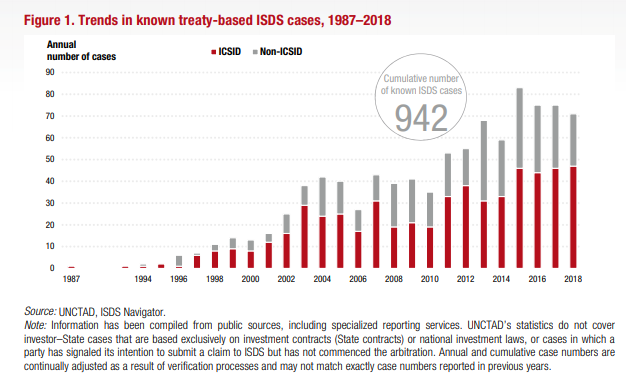

IIAs include the possibility for a foreign investor to take legal action against a state in an international arbitral tribunal – and not through the domestic judicial system – if the acts of the public power are perceived to violate the terms of the international treaty.

The fact that multinational companies have the possibility of accessing this mechanism for resolving disputes is very often contentious, because the interpretation of investor rights is very broad. That is probably why the number of disputes has risen significantly over time. As an example, Philip Morris sued Australia and Uruguay for damages after these two countries introduced anti-smoking measures, claiming that the latter had significantly diminished the value of the company’s international investments. As another example, Veolia sued Egypt, arguing that the minimum wage increase decided by the government in 2011 was prejudicial to the company’s local operations. In these specific cases, the claims of both multinational companies were rejected, but this creates a climate of uncertainty for states wishing to introduce measures that are by all appearances legitimate, since they aim to protect workers, health or the environment, but could affect the profitability of an international investor. This is called a “chilling effect” of IIAs that hinders and slows public power.

Getting back to the present, the SARS-Cov-2 epidemic has brought this controversial issue back to the surface, because the lockdown measures imposed by the different states could be perceived as a violation of the clauses contained in the IIAs pertaining to the right to equitable and non-discriminatory treatment, to safety, or to compensation for direct or indirect expropriation. Nevertheless, it should be emphasised that time and again, international courts of arbitration have granted states considerable margin of discretion to determine the areas that legitimately require their intervention, particularly during major crises. Public power is also influenced by private-sector lobbying. For instance, a number of companies from the energy or automotive industries are requesting a loosening of environmental standards to help them weather the current economic crisis. In the United States, the petrochemical industry wants more widespread use of single-use plastic bags and wrappers. In France, the main federation of employers, Medef, wants a “moratorium” on the implementation of environmental measures. If these requests were granted, this would prove that the French Foreign Affairs Minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, was right to fear that “The world afterwards will be very much like the one before, only worse”.

In a constitutional state, public power is more often exercised under the downstream control of the domestic judicial system, but is also sometimes subject to international investment law, which is not as clearly defined as domestic law. Moreover, upstream, certain private players with financial resources far superior to those of the average citizen can influence the actions of the state. The democratic legitimacy of international arbitration tribunals or private lobbying – the latter being sometimes considered legal corruption – is dubious. Fortunately, states and their stakeholders have other means of recourse to reassert their sovereignty. IIAs can be revoked or renegotiated to better establish the limits of the state’s exclusive regulatory space. The activities of lobby groups can be made more transparent.

Thus there is no requirement for the public power to yield to the private power nor for the greater good to be sacrificed to serve narrow private interests, whether these be domestic or international.