In these times of great uncertainty, everyone is seeking to better anticipate the future. In the military and intelligence fields, it is striking that, besides tactical or technological solutions, top officials are adopting transdisciplinary approaches similar to consilience.

During the Bastille Day ceremony on 14 July 2019, the inventor Franky Zapata flew over the Champs-Elysées on his jet-powered flyboard under the astonished gaze of spectators and onlookers. In some respects, it was a case of fiction becoming reality as humankind’s age-long dream of flying through the air was accomplished so simply. Behind this spectacular event hides a radical shift: the French military is now turning to external resources to anticipate and plan for its future.

Among these, one of the most recent is the Agence de l’innovation de défense (Defence Innovation Agency) founded in September 2018 and headed by Emmanuel Chiva. This ENS alumnus is a doctor of biomathematics specialised in fields ranging from artificial intelligence to biomimicry. The goal of this outward-looking agency is to foster experimentation and innovation in all fields necessary to support and improve the capabilities of the French armed forces. In July 2019 the agency announced that it would be hiring four or five science-fiction writers to create a “Red Team”. The “Red Team” concept is borrowed from the cybersecurity lexicon. It denotes a group of people tasked with challenging the security of a company’s IT systems and developing staff awareness of the risks of hacking and cyberattacks. In the case of France’s Defence Innovation Agency, the job of this Red Team of visionary authors will be to come up with scenarios of disruption for the military, or in other words to imagine potential future threats but also propose solutions for future strategists. Hiring civilians who are not formatted by the military encourages out-of-the-box thinking to identify risks and solutions.

In truth, this French innovation is largely inspired by examples abroad, including the United States. In fact, the comparison between the two countries is interesting. Indeed, the American military publishes regular reports setting out forward-looking scenarios. In the wake of the “Revolution in Military Affairs” launched at the start of the new century, they too cross-link the expertise of different sectors. These reports often focus on the contribution of technological innovations capable of guaranteeing the United States military supremacy: drones, satellite surveillance, “smart” missiles, etc. The fact is that these days the art of war is being radically altered by new threats, including asymmetric conflicts. As pointed out by Bertrand Badie in a recent publication, what makes modern-day conflicts so different is that they are not so much the expression of a competition between major powers anymore, but rather the symptoms of a weakening of states when they are not simply a reflection of their decomposition. Think Libya, Somalia and Syria at the moment. It is understandable, then, that the US military high command is now seeking new ways and strategies to address these threats. In any case, there exists an abundance of literature from the ranks of the American military discussing the futures of warfare that are possible if an interdisciplinary approach is used.

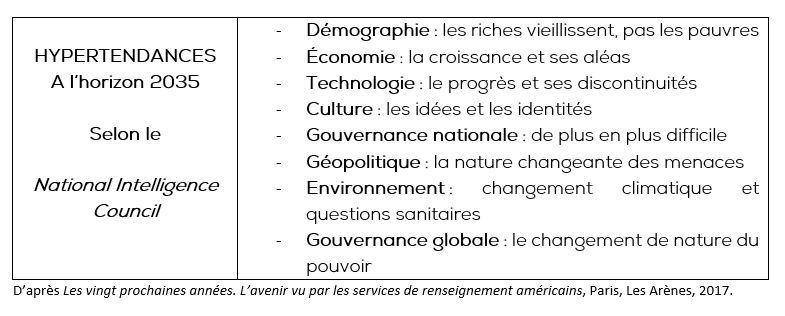

In addition to the military, it is worth noting the importance of intelligence on the other side of the Atlantic, particularly the National Intelligence Council (NIC) whose core mission is “intelligence integration”. Established in 1979, this agency, which has been reporting directly to the White House since 2004, is essentially composed of members of the CIA but also works with external experts. Since 1997, the NIC has been producing a forward-looking report every four years about the world to come. This report is presented to the president of the United States at the start of their term. Drawing on a vast network of collaborators and using a bottom-up method, the authors seek to put forward various possible scenarios about how the world will be over the coming years, with the aim of informing the decisions of the newly elected U.S. president. To do this, they converge different areas of knowledge and identify megatrends that are already structuring our world and will continue to do so in the future. These different areas include demographics, economics, technology, culture, geopolitics, the environment and governance.

Convergence is not juxtaposition. Because after having identified these megatrends, the authors of the report interconnect them in order to consider several futures that might be possible on a five and 20-year scale. Actually, it is worth noting that the latest NIC report is the bleakest of all those published to date, since it considers the possibility of a planet where globalisation has given way to isolationist continental zones… The idea that guides this type of process overall is common to all forward-looking processes. It is underpinned by the premise that the future is not yet written: it is not the continuation of the present, but rather what is different from it. Gaston Berger, founder of the school of foresight (la prospective) in France, summarised it in a pithy statement: “Tomorrow will not be like yesterday. It will be new and will depend on us. It is less about discovery than it is about invention.”

In conclusion, in their own distinct ways, the examples of the French military and of American intelligence illustrate the importance of consilience; drawing from different fields − technology, science-fiction literature, military and security concerns − and converging towards a common goal; giving the armed forces and political leaders the capacity to anticipate and deal with threats that are as yet unknown.