On 9 August 2021, the IPCC published its latest report. It presents troubling possible climate futures, highlighting in particular an alarming rise in temperatures despite the commitments made by governments. It is clearer than ever that the action, or inaction, of States is pivotal in this matter. Analyses of the geopolitical consequences of global warming abound, but should the word order be reversed? After all, is it not geopolitics that is influencing climate change?

A worrying state of affairs

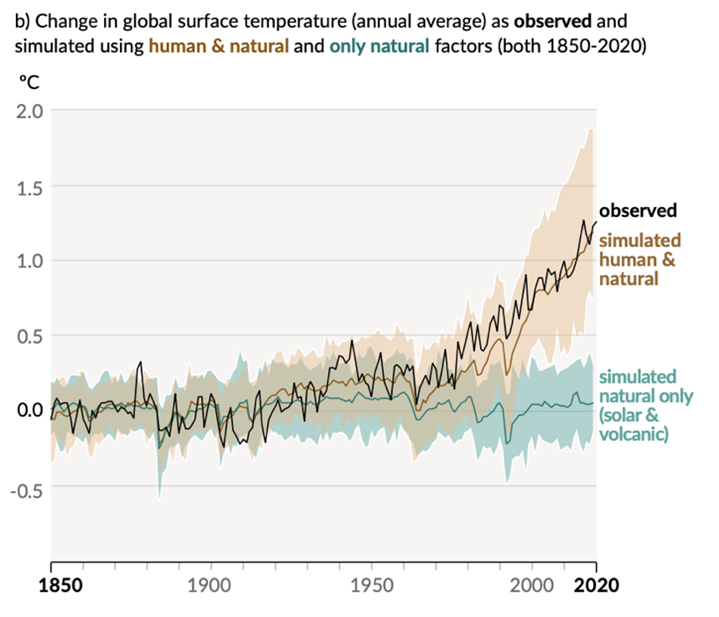

Condensing more than 14,000 scientific publications on climate, the IPCC report marks another step forward in evaluating climate change, its determining factors and its possible consequences. The compiled research all points in the same direction, establishing that human activity is indeed what explains the unprecedented warming of our planet over the last decade. As the graphic below shows, unlike human activity, so-called “natural” factors such as solar and volcanic activity have very little impact on climate.

The report also shows that temperature levels are already 1.1 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and should exceed 1.5 degrees by 2030. Remember that the goal of COP21 was to limit the increase in global average temperature on Earth to 2 °C or even 1.5 °C by… the end of the century! It also appears that the past decade was the warmest in 100,000 years.

An interactive atlas to point out risks

What makes these global and massive changes difficult to grasp is their geographic heterogeneity on the one hand, and the fact that they will be occurring in a future that seems very far off. For many people, particularly in rich countries, global warming can be summed up in two offhand remarks that justify the current lack of action: “That’s someone else’s problem!” and “I won’t be around to see it!”. The IPCC has made a new tool available to change this attitude. It is an interactive atlas that shows, for each region, how the different elements of climate (temperatures, rainfall, etc.) are likely to evolve over the coming decades, thereby presenting a concrete picture of what is in store. This graphical simulation shows that global warming is happening faster in some parts of the world, particularly in the Arctic and Antarctic regions or the Mediterranean, where periods of drought will have potentially dire consequences for food security.

It is worth noting that extreme weather events – heatwaves, storms, floods – are very sensitive to small variations in global temperature. That is why, from a climate perspective, the world in which we are living in 2021 is no longer the same as it was in 2010. Certain elements are already irreversible: glacier melt has begun and it is occurring quickly and continuously. This will lead to a rise in sea levels, which have already risen by 20 cm since 1900. As for heatwaves, which are now occurring at unusual times of the year and in unexpected places, they will last longer and become more intense, accompanied by a host of detrimental consequences. The spectacular fires of the last few years are just one of many signs of this.

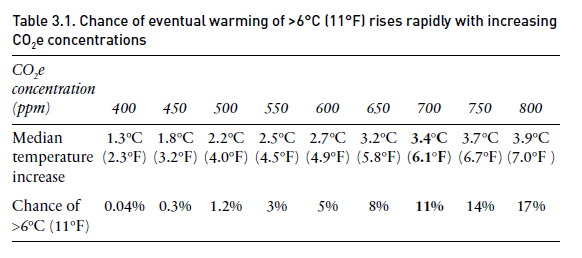

In sum, if global warming goes unchecked, the planet could very quickly reach tipping points where the warming leads to even more warming. Indeed, as underlined by Martin Weitzman, the probability of such a climate shock – where the rise in temperatures could exceed six degrees Celsius on average on Earth – increases proportionally to the rise in CO2 concentration in the atmosphere.

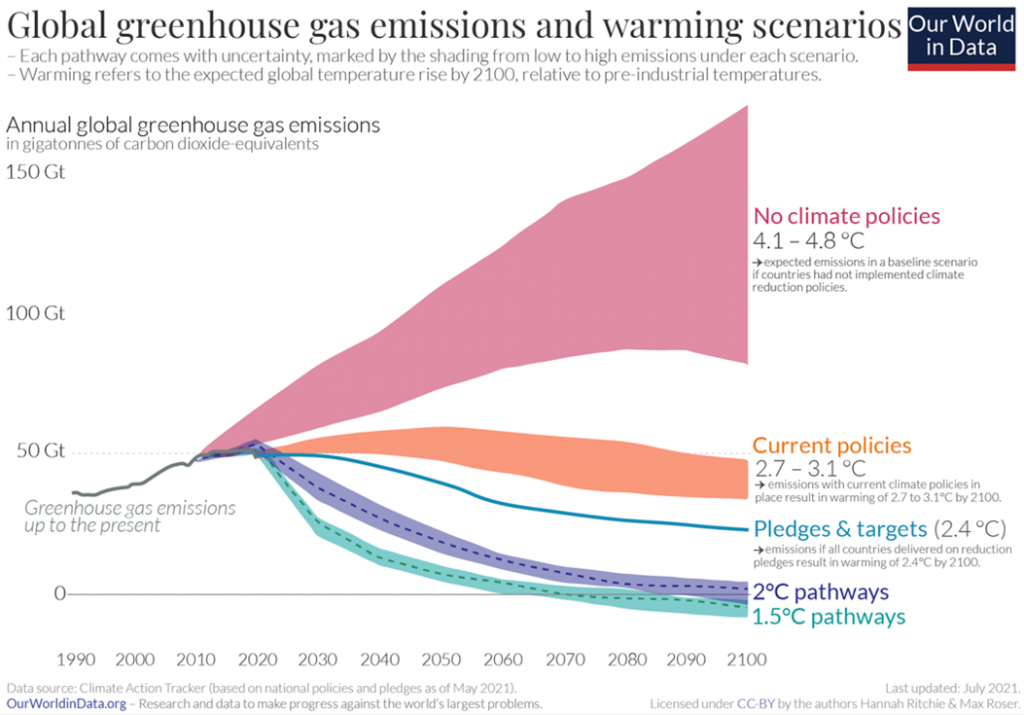

Five scenarios that largely depend on the international geopolitical context

To avoid triggering a paralysis effect in reaction to these announcements – which would undoubtedly lead to fatalism and inaction – the IPCC report provides geo-climactic and socio-economic narratives or scenarios. These are underpinned by the resolutely optimistic and galvanizing idea that humanity is not powerless against climate changes. The report insists on the fact that the inertia of the climate system is not as substantial as first believed. And even though the evolution over the coming decades is already largely unavoidable – due to the existing accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere –, humans can still very much mitigate the situation… or let it go unchecked, depending on how proactive and coherent the world’s leaders make their climate policies. Of these five scenarios, only one (called “SSP1-1.9”) would make the COP21 objectives attainable; it requires achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. In the worst-case scenario, current emission levels are tripled, resulting in a temperature increase of 4.4 degrees Celsius. For comparison, just five degrees (more) currently separate us from the last ice age…

United action, a critical challenge

The problem is that the success of global warming mitigation policies hinges on taking concerted collective action globally. By drawing on “game theory” tools, the social sciences underline that this type of action is extremely difficult when individual rationality conflicts with collective rationality. Thus, although it is in everyone’s interest to prevent global warming, we all prefer to have others bear the costs, particularly if the benefit-cost ratio seems unfavourable. In that case, what are the solutions to break this stalemate frequently illustrated using the famous “prisoner’s dilemma”?

An international community yet to be invented

The COVID-19 crisis has demonstrated that we cannot simply count on rich countries showing solidarity to the poorest to resolve this collective action issue. As the French political scientist Philippe Moreau-Desfarges points out, the “international community” does not exist, or at least not yet: it is more of an artefact without substance invoked, for example, when dramatic events occur and it is said to be “deeply sorry” or “shocked”. The reality is that there is no supranational entity with the power necessary to compel a State to act for the collective good rather than out of self-interest.

Going towards a geopolitics of cooperation

Nevertheless, while the “international community” does not exist yet, it could emerge from ecology as Hubert Védrine stated in his essay, Le monde au défi. While no values are truly shared planet-wide that could provide the foundation for a sense of community, we do all share a common destiny that global warming is threatening. Put differently, the geopolitical climate would need to cool down too, to become more “cosmopolitical”, i.e. a system of international relations more oriented towards cooperation than rivalries and tension.

Ecology as a “realistic” issue

For the moment, clearly, the “realistic” vision is prevailing; the one where, driven by their own interests, States only take climate-related action if they see some benefit in it for them. For years, that was not the case. Did President Bush not declare in 1992 that “the American way of life is not negotiable”? However, it is possible that we may have now reached a turning point: not only are extreme weather events multiplying and affecting rich countries and those with strong economic growth, but scientific consensus is emerging and public opinion is in favour of greener policies. The high cost of climate change is becoming undeniable.

Economic costs of climate change

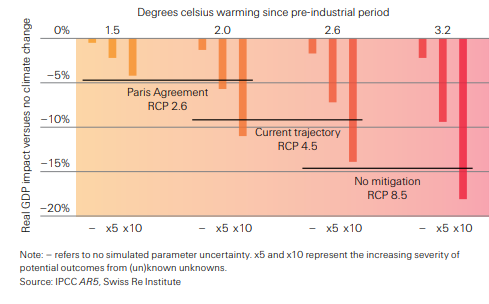

The insurer Swiss Re estimates that the cumulated losses could represent 20% of the global GDP in 2050 (24% for China, 10% for Europe and the United States). Former central banker Mark Carney points out that these figures are probably underestimated, as they do not take into account the possible emergence of pandemics, mass migrations or conflicts. Faced with this alarming prospect, rich and polluting countries could decide to form an international coalition because it would be unilaterally in their interest to contribute to it. And this would have all the more influence as their economic power would enable them to impose their environmental rules through a carbon border adjustment mechanism. Economic globalisation would thus make forced international cooperation possible, at the instigation of the major powers.

Although we are not there yet, there is no doubt that COP26, to be held in Glasgow in November 2021, will be a high-stakes conference and that it will draw on the conclusions of the IPCC report. Even if all States agree collectively to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, discussions about the distribution of the remaining carbon budget or aid to support the energy transition in poor countries are likely to be heated. There again, it will be realism against cosmopolitanism.