In the aftermath of the pandemic crisis, a number of already weak countries will fall in deep economic and social distress. That raises the question of the efficiency of official development aid coupled with debt relief to pull countries out of poverty when bad governance is endemic. Most of the aid recipients exhibit very poor governance records, with a toxic combination of large wealth gaps, weak institutions, large corruption, and authoritarian regimes. The solution is to make development aid dependent on robust and monitored improvement in governance in developing countries, hence conditioning debt relief and aid flows upon long-term commitments regarding institutional strengthening and capacity building, as well as civil rights protection.

Enhancing good governance in EU’s developing country partners

The EU’s development policy has modest impact on sustainable and inclusive development prospects in countries that benefit from aid programs and debt relief negotiations. Corruption costs the European economy around €120 billion euros per year, reportedly. However, turning a blind eye on institutional weaknesses in developing countries generate additional indirect costs due to socio-economic and political turmoil. Promoting good governance in aid recipients would boost the effectiveness of the EU’s € 67 billion a year budget to help overcoming poverty and advance global development. Governance-driven development aid would help the EU be better accountable to its citizens who make solidarity initiatives possible. Enhancing governance reforms is in the EU’s own political, economic and security interest.”

The impact of the pandemic crisis on institutional weakness in developing countries

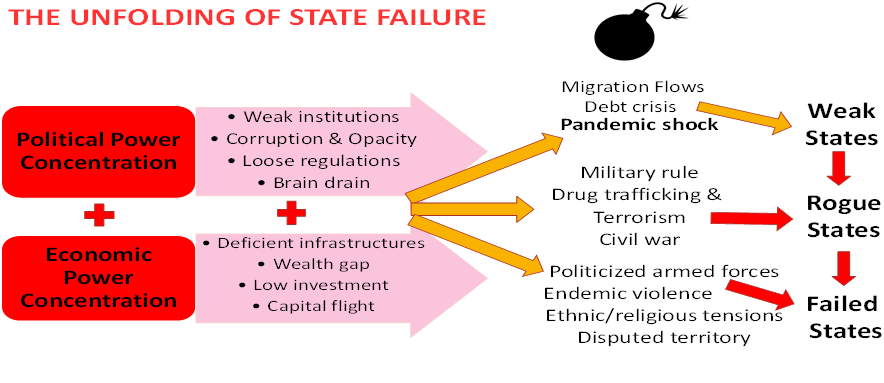

The issue of enhancing governance in the EU’s development aid policy is all the more important in view of the “scissor effect” that many developing countries face today: larger financing requirements coupled with deteriorating governance and autocratization. In many recipients of EU’s development aid the pandemic crisis creates a « precipitation » of accumulated institutional and structural weaknesses to trigger a systemic shock, a sort of dreadful crystallization, i.e.; a Great Collapse. Many economies had pre-existing vulnerabilities, which are now intensifying, representing potential headwinds to any inclusive recovery. The World Bank announced in the beginning of 2022 that downside risks cloud the outlook for developing countries. The IMF’s warning is almost brutal: “Faster US Fed rate increases could rattle financial markets and tighten financial conditions globally, leading to capital outflows and currency depreciation in emerging markets”. The WEF’s latest Global Risks Perception Survey stresses that societal risks—in the form of “social cohesion erosion”, have worsened the most since the pandemic began. Clearly, the much weaker social fabric in many African, Central European, and Latin American countries tends to undermine public trust and democracy, while promoting autocratic regimes. One only needs to look at Venezuela, Mali, Niger, Burundi, Burkina Faso, Yemen, Syria, Libya, Iraq, Nicaragua, and Congo for that matter. And what about Tunisia, Lebanon, Algeria, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, and Bolivia?

These “weak states » are unable or unwilling to provide public goods due to institutional flaws. These common goods are precisely crucial to transform economic growth into equal development opportunities, i.e., health and education systems, democratic institutions, transparency and accountability. A number of developing countries are struggling with a toxic brew of corruption, low public trust, and repressive regimes. The most obvious examples are Myanmar, Zimbabwe, Haiti, Cameroun, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Sudan, Angola, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea… among many others. Institutional weaknesses generate a crisis of social mediations: parties, unions, political institutions, and local elites lose credibility and trust for addressing social frustration and demands, hence rising tensions. Where institutions cannot address and channel the citizens’ demands, the resulting deficit of social transmission belts generates turmoil, repression, and violence.

Why is the pandemic crisis accelerating risks of state failure in EU’s aid recipients?

The worldwide pandemic illustrates four main trends that can precipitate a structural collapse in weak states: The first driver is a sharp decline in trade, tourism, capital, and foreign investment flows. The pandemic shock emerged in a long-term trend of declining growth and large indebtedness, accompanied by weak investment, so-called secular stagnation. In addition, rising inflation increases the risk of stop & go policies, with negative consequences on development prospects. There are many converging signs of a collapse of international cross-border capital inflows for developing countries. The second driver is looming debt crises. The 45 sub-Saharan African countries boast rising debt servicing costs with External Debt/GDP ratios that reach 45% of GDP currently, back to 1990 levels. Worse, their ratio of External Debt to export revenues is also similar to its level in the early 1990s, around 225%, erasing three decades of debt relief. A number of weak countries will sink into sovereign bankruptcy due to a combination of risk aversion in capital markets, higher rate of interests, and volatile export receipts. Venezuela, Puerto Rico, Argentina, Ecuador, Lebanon, Belize, Suriname, and Zambia are already in default. The third driver of state collapse is growing wealth gaps: Weak and failed countries have all very high GINI indices, up to 50 (Zimbabwe, Angola, and Mozambique) and even close to 60 (Zambia, Sao Tome, and CAR). The level of wealth distribution has been a key factor determining resilience in the public health crisis, due to its correlation with the quality of national health systems and their public access. If past pandemics are any guide, the toll on poorer and fragile people will be large, particularly in weak states in sub-Saharan Africa. The fourth driver is endemic corruption.The pandemic crisis has exposed large deficits of governance in Africa and Central America, which is striking in oil and commodity-driven countries. The vast majority of weak countries are below the median score of the corruption index of Transparency International. Corruption is unabated despite decades of official development aid (ODA) programs.

The risk of state failure imposes a reassessment of EU’s development aid policies

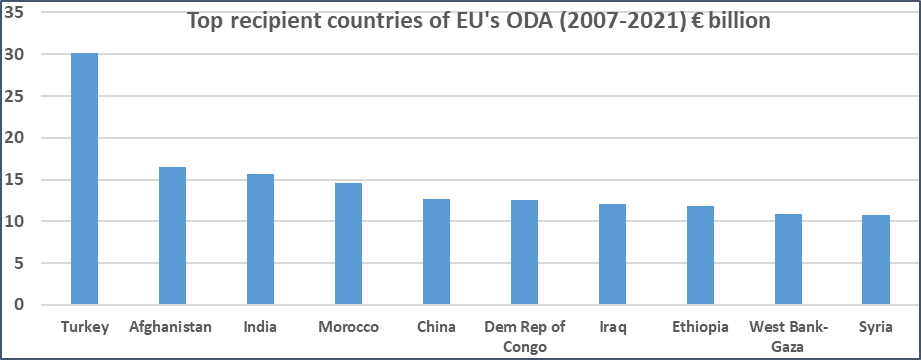

n 2022 and beyond, a number of already weak countries will fall in deep economic and social distress. That raises the question of the efficiency of official development aid coupled with debt relief to pull countries out of poverty when bad governance is endemic. In response to the unprecedented challenges posed by the pandemic and at the urging of the IFIs, in April 2020, the G20 launched the Debt Service Suspension Initiative to provide liquidity support for low-income countries. In 2020, ODA rose to $158 billion thanks to donor countries’ efforts to combat the impact of the pandemic, including $39 billion of net bilateral ODA flows to Africa. The EU and its 27 Member States provided €67 billion in ODA, with the altruistic objective of strengthening weak states. The problem is that most of the aid recipients exhibit very poor governance records. EU’s ODA recipient countries are typically among those that combine poverty, large wealth gaps, weak institutions, large corruption, and authoritarian regimes.

Toward an EU’s international guardianship?

As the European Commission has relaunched the public debate on the review of the EU’s economic governance framework in 2022, the opportunity is good for a thorough reassessment of official aid programs. The objective should be to make ODA dependent on robust and monitored improvement in governance in partner developing countries. The instrument would be conditioning debt relief and aid flows upon long-term commitments regarding institutional strengthening and capacity building, as well as civil rights protection. Far from any post-colonization subordination, guardianship would entail close concertation between the EU, foreign creditors, IFIs, civil society, and local governments. Disbursements and debt relief would fund domestic investments in high-priority social sectors. Greater prioritization of spending would be central in this new aid strategy. Developing countries would then be better equipped to transform growth into sustainable and inclusive development. Donor countries would gain the insurance that their multi-billion euro aid programs are not recycled in their capitals through capital flight.

This article is derivated from a policy paper written by Michel-Henry Bouchet for the CIFE (Centre international de formation européenne).