The coronavirus epidemic has generated an abundance of literature on past pandemics. In these publications, the Justinianic plague in the 6th century is often described as one of the deadliest in history. Yet a recent study challenges this idea by applying a rigorous and multidisciplinary scientific method. It is a remarkable example of consilience.

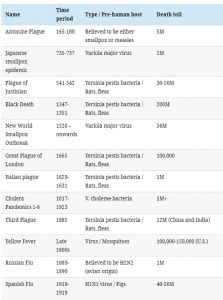

As we are tragically reminded by the COVID-19 health crisis, human history is regularly marked by periods of pandemic. Currently, numerous publications point out the historical similarities between the situation we are experiencing and the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918-1919 or the Black Death in the 14th century. This is unsurprising, as these pandemics caused tens or even hundreds of millions of deaths in a world population that was a lot smaller then than it is today. Curiously, the Plague of Justinian – named after the emperor who reigned over the Byzantine Empire from 527 to 565 – is rarely mentioned despite a terrible death toll usually estimated at thirty to fifty million for a global population of 200 million at that time. The plague affected the Middle East, North Africa and Europe to such an extent that historians frequently suggest it may have caused the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire by producing a wave of political disruptions.

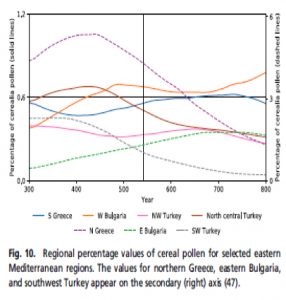

Of course, a pandemic’s influence on history depends on the number of deaths it causes. It would be imprudent to explain the fall of the empire if the purported high death toll caused by the pest proved to be modest. Guided by this line of thinking, a recent study has rekindled the debate. The researchers who conducted it re-examined the direct and indirect markers indicating the extent of the ravages caused by the Justinianic plague. In a thorough exercise in consilience, they studied the references to the epidemic in ancient inscriptions and texts. They also evaluated its impact on the number of laws promulgated, the coins in circulation, the number of papyruses produced in Egypt, and the presence of mass graves. Finally, as the above graph shows, they were able to measure whether the pollen levels associated with grain cultivation had dropped.

The findings of their research are incontrovertible: there is no sign of a break indicating a sudden halt in farming or trade, nor of any decrease in population. In other words, in their observations there is no evidence to corroborate the usual estimates of the death toll the Justinianic plague might have caused. How do we explain the wide gap between these conclusions and those of historians of Late Antiquity who describe this plague epidemic as one of the deadliest in history? The reason is that these historians refer mainly to written, epigraphical and archaeological sources, but only rarely use advanced scientific methods like the ones used by the researchers who conducted this groundbreaking study.

Using this multidisciplinary approach, the authors applied the scientific method. As Karl Popper pointed out, theories must be tested against facts through a falsification process. There is no absolute truth in science, there are only corroborations. One must accept this epistemic uncertainty, but adopting a consilience approach is one way to reduce it.