What if you bought a piece of “All I Want for Christmas Is You”?

You might soon enjoy listening to All I Want for Christmas Is You even more. Like many other songs, Mariah Carey’s hit could soon end up on a music marketplace and become yours to own, in part. Music is becoming a financial asset, accessible both to funds and individual investors. But is it really a worthwhile investment?

When we think about investing, it is usually shares, bonds, real estate or commodities that spring to mind. But what if I told you that, if chosen wisely, the music you listen to every day can offer higher annual returns than some traditional investments?

Every day, we listen to music almost without noticing: on the radio, in supermarkets, bars, clubs, films and even elevators. Much of this listening generates royalties. These revenues go to songwriters, composers, producers – in short, to anyone who holds rights.

Mariah, the Unstoppable Bet

Take a song like All I Want for Christmas Is You by Mariah Carey. Released in 1994, it generates between two and three million dollars each year (Billboard), thanks solely to its annual return to Christmas playlists and films. This single track generates a steady, recurring income stream, largely independent of economic cycles.

If you heard it during a family gathering, even without realising it, you contributed to this sizeable pot, which is then distributed among rights holders according to their shares.

In this world, if there is one thing you can count on every year, it is this song.

For those who own the rights, it is a stable and predictable source of income largely insulated from market volatility.

This is why investors and institutions have turned their attention to buying music rights from artists or labels, either to generate returns or to diversify their portfolios.

My name is Bonds, “Bowie Bonds”

The idea is not new. In 1997, singer David Bowie became the first artist to turn his music into a financial product. He borrowed money from investors, promising to repay them using future revenues generated by his songs. These securities functioned like bonds and were known as ‘Bowie Bonds’. Investors lent him US$55 million and, in return, they received a share of the royalties from his albums for a period of several years.

Read also: Prof. Sotiris Manitsaris: “AI can redefine how music is performed”

Since then, the movement has gathered momentum. Funds such as Hipgnosis, Primary Wave and KKR have invested several billion dollars in the catalogues of major artists including Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Queen, Shakira and Michael Jackson. More recent players, such as Alternative Partners AG and ICM Crescendo Fund, have also entered the market with more targeted investments, offering clients attractive returns that are weakly correlated with equity markets.

For example, in 2023, singer Justin Bieber sold his entire music catalogue to Hipgnosis Songs Capital for an estimated US$200 million. Katy Perry sold Litmus Music the rights to five albums (released between 2008 and 2020) for around US$225 million.

The Instinct of Finance. The Finance of Instinct.

For an investor, assessing the value of a music catalogue has little in common with analysing a stock or a conventional company. Buying music rights, a so-called ‘alternative’ asset class, is not just about reading balance sheets or calculating growth rates. It is also about betting on tastes, emotions and fleeting cultural trends, sometimes over decades.

Where traditional finance relies on stable figures and mathematical models, investing in music requires a nuanced understanding of audiences and how tastes change. It is a field where financial analysis meets artistic sensibility. The objective of investment funds may appear straightforward: buy at the right price to generate attractive returns. In practice, though, it is far more complex.

Fund managers look at both objective data (streaming figures on platforms, revenue generated, use in advertising, or geographic distribution of listeners) and more subjective elements such as the artist’s career, current musical trends or the impact of new technologies on listening habits. This mix of data and instinct makes each investment decision unique.

There are also macroeconomic risks: the need to invest when interest rates are low; to exercise caution regarding exchange-rate fluctuations (to avoid acquiring a catalogue denominated in euros when the currency is weakening); to diversify a portfolio across genres, artists and markets; as well as technological risks stemming from listeners’ heavy reliance on streaming platforms.

A Legacy That Sings

In short, many parameters make investment in music catalogues a complex exercise, but one that can be highly profitable for well-informed investors.

That said, this asset class is not limited to large funds; it is also accessible to individuals looking for new opportunities. Several platforms allow users to explore online catalogues that rights holders are looking to sell. Royalty Exchange remains a go-to in the sector, connecting sellers and investors and offering a wide range of genres, from hip-hop and electronic music to country and film soundtracks.

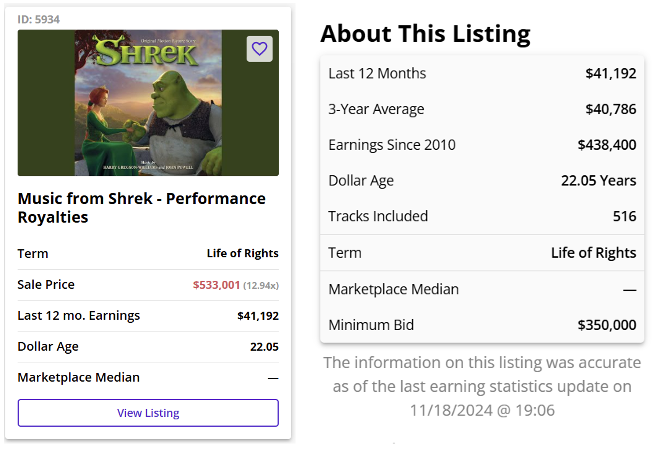

An example of a catalogue sold in 2024:

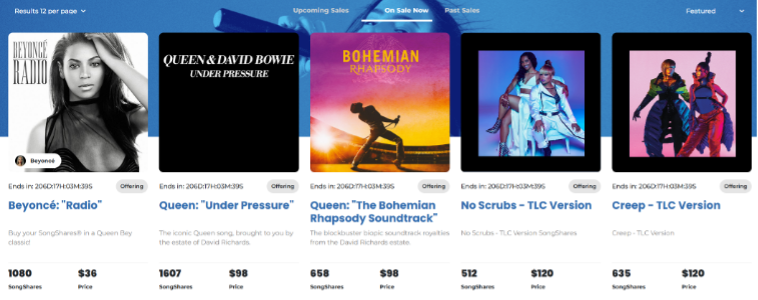

SongVest is another marketplace popular with investors, as it allows them to purchase small fractions of music rights. By contrast, Royalty Exchange generally offers entire catalogues through an auction system. Here is a selection of the listings currently available on SongVest:

Other marketplaces exist in Europe, the top two being ANote Music and Bolero. ANote Music allows investment in established catalogues via an auction system or through a secondary market. As for Bolero, it goes even further in democratising access to investment opportunities, by offering the ability to purchase fractions of rights for just a few euros.

Like any investment, putting money into music carries risks, and it is essential to carefully analyse catalogues and their potential before getting started.

However, while this alternative asset class may appear riskier, music endures over time. How many companies can you name that have endured across generations the way so many songs have? As the composer Edward Elgar once said: ‘Music has the power to transcend time and leave a lasting legacy.’ Now, you have the opportunity to make that legacy work for you.