“I’m my own banker.” This slogan for a French neobank sums up the concept quite well. Will the all-digital services offered by neobanks replace or complement those offered by traditional banks? Their recent rise raises questions about the future of the banking sector.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, you may not even have known about them. Neo-banks, whose services are exclusively digital, have seen their business boosted by this forced acceleration of digitalisation. But for many, they remain an enigma, even a source of mistrust. Even though their influence is likely to grow in the years ahead. And no major neobank in Europe (having achieved critical mass) has recently gone bankrupt, unlike some traditional banks (Crédit Suisse, for example).

Neobanks, a good account

There are two types of neobank: those that do not have a banking licence and work in partnership with a traditional bank, such as Up bank in Australia, which relies on Bendigo Bank, and neobanks that have their own banking licence, such as Xinja and Volt.

What they all have in common is that they are fintechs or are associated with fintechs, i.e. companies that take advantage of technological advances to provide more practical, efficient and customer-focused banking services. This simplifies the often complex processes associated with traditional banks. Their digital interfaces are more intuitive, user-friendly and offer a wide range of personalised features.

Read also: Innovation needs financial competition, not deregulation

Against a backdrop of rising interest rates and the collapse of some of the ‘big names’ in traditional banking, are the business plans of neo-banks likely to disrupt the banking landscape and put them in a dominant position?

Academic research and consultants offer us a few pointers.

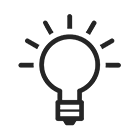

According to the Statista platform, the market share of neobanks in Europe is expected to reach 11.1% in 2023. This means that around 11.1% of all bank accounts in Europe will be held by neobanks. In the United States, the market share of neobanks is expected to be even higher, reaching 15.5% in 2023. Admittedly, we are still a long way from a majority market share, but some consultants such as Grandview research see exponential growth between now and 2030.

The landscape of neobanks in Europe is evolving very rapidly indeed. It is estimated, very roughly, that there are over 150 of them today. Some European countries, such as the UK, Germany, France, Spain, the Netherlands and Sweden, have an ecosystem conducive to financial innovation and are among the biggest markets for neobanks.

Neobanks don’t like a vacuum

Neobanks are inherently digital. This means they can significantly reduce overheads, which translates into savings passed on through better interest rates and lower fees.

In addition to favourable financial conditions, neobanks frequently collaborate with fintech companies to offer value-added services such as automated savings, investment options and real-time spending information that respond to changing customer needs and preferences. Neobanks are known for their agility and ability to adapt quickly to market trends and customer demands. Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, machine learning and open banking APIs are being adopted rapidly (APIs facilitate communication between two IT systems, such as the inclusion of Google Map on user interfaces). The capacity for continuous innovation is therefore key to a neobank retaining its ‘first mover advantage’.

Neobanks often focus on niche markets or customer segments that are poorly served by traditional banks. For example, they can meet the needs of digital millennials, the self-employed or small businesses by offering tailor-made solutions ranging from flexible lending options to fast and simple account opening. These solutions also include business expense management, international payments, automated invoicing and simplified accounting tools, as well as integration with third-party services and providers.

The solid performance of the French neobank Qonto is based, for example, on its exclusive focus on the specific needs of SMEs and the self-employed.

Autonomous but not independent

In addition to the psychological barrier of not having a physical presence, many neobanks suffer from a lack of trust and brand recognition. Concerns about security, data confidentiality and the stability of neobanks are also holding back their development.

Neobanks often rely on partnerships with traditional banks or other financial institutions to provide certain services (such as deposit insurance or access to payment systems). This dependence is potentially their greatest weakness, as it can call into question the continuity of services. It also generally leads neobanks to offer a more limited range of products.

Neobanks, the sin of youth

A study by the Banque de France entitled “Neobanks in search of profitability”, published in 2020, shows that some small neobanks are experiencing financial difficulties. This lack of profitability is linked to the cost of attracting new customers to make up for the lack of brand awareness (subsidising new customers, either by granting bonuses when they open an online account, or by matching funds paid when new customers are sponsored).

Neobanks are faced with major investments to develop their digital and technological infrastructure. As they are essentially digital entities, they face heightened cybersecurity risks, requiring massive and ongoing investment to optimise their operational robustness and resilience in the face of recurring cyber-attacks. Complying with regulatory requirements, obtaining the necessary licences and meeting capital adequacy standards can be complex and time-consuming for new banks.

Faced with these financial and transactional costs, neobanks sometimes err on the side of optimism, overestimating customer growth.

However, these “early cycle” costs seem to diminish over the years as we learn by doing. The latter are mainly financed by the Banque de France, which also points out that “there has been a gradual improvement in profitability over time”.

Real estate, an empire to be built

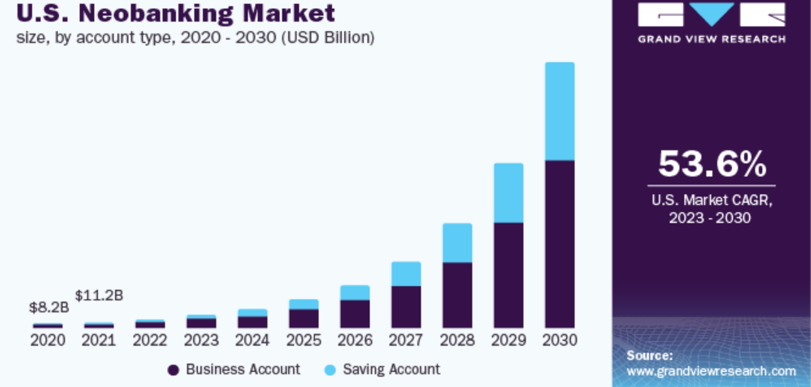

The global neobank market is relatively fragmented, but remains dominated by a few major players, thanks to technological advances and innovation.

The current rise in interest rates is strengthening the hand of traditional banks in their competition with neo-banks. The difficulty of the mortgage market remains a weapon for traditional banks when it comes to re-opening accounts. Although some neobanks offer mortgages, this is not a regular feature of their business plans. Neobanks generally concentrate on basic banking services, such as current accounts, payment cards, money transfers and savings.

However, it seems inevitable that mortgage lending will have to be developed if the neo-banks are to survive… According to a report published in 2022 by the American Bankers Association, mortgage loans represented 30% of the total revenue of US commercial banks in 2021. This means that for every $100 in revenue generated by a traditional bank, $30 came from mortgage loans. What’s more, traditional banks tend to attract customers through mortgages. They can be an excellent way of establishing long-term relationships with new customers. Mortgages are therefore an element of inertia in the renewal of the banking market.

The bank we want to recommend… to those who don’t have one?

The last few months have seen a number of bank failures (Crédit Suisse, First Republic, Silicon Valley Bank), all banks with numerous branches and dominant positions in their respective regional markets. In each case, these were traditional banks faced with rising interest rates (a fall in the value of their bond portfolios), a lack of diversification among their customer base or self-fulfilling liquidity concerns (investor anxiety in a context of rising interest rates, falling stock market prices, bank runs and subsequent deposit withdrawals).

Read also: Digital money, private and public: is this the face of the future?

Stock market volatility has played a destabilising role here. Although several neobanks have opted for an IPO to finance their expansion and increase their visibility, most are not listed on the stock exchange and have therefore escaped any instability.

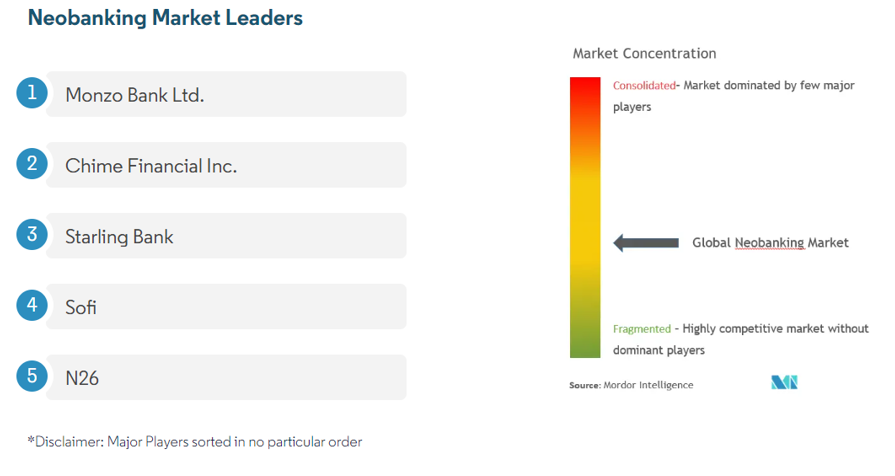

In the medium and long term, neo-banks also seem well positioned to offer lucrative opportunities for expansion, such as strengthening online services to the unbanked population in emerging economies, but also in developed countries! It is estimated that 1.5 billion adults worldwide have no bank account! A phenomenon that is also present in many European countries, even if South-East Asia clearly appears to be the part of the world with the greatest development prospects.

On the lookout for the slightest opportunity

Neobanks have huge growth potential, but their penetration of traditional banking markets is not yet a given. In this respect, the recent changes in the financial landscape (rising interest rates and bank failures) do not yet appear to be a “game changer”. Competition in the banking sector is set to increase, but home loans appear to be an obstacle to the development of these new digital “pure players”. The practices involved in repatriating accounts for home loans do not fall within the scope of possible anti-competitive practices.

When interest rates fall, however, the neo-banks could play a major role in the loan renegotiation market and present attractive opportunities. In September 2000, the traditional banks were warned and penalised for a non-aggression pact (an illegal agreement) that resulted in a failure to canvass customers for loan renegotiations. The future sequence of interest rate cuts will be decisive for the neo-banks, and the players involved are on the alert.