The “Clash of Civilizations”, an oversimplification of World Order?

We sometimes say that the simple things in life are often the best. But does this also apply to the sciences? In 1993, Professor Samuel Huntington attempted this in geopolitics. His theory of international relations was based on a division of the world into “civilisations”. Oversimplification or simplicity?

In 1329, the Franciscan monk William of Ockham formulated the principle of parsimony, according to which the simplest solution is usually the best. In other words, unlikely explanations for a system should be ruled out. This emphasis on simplicity is not unique to Ockham: from Aristotle to Montaigne and the contemporary philosopher Gaspard Koenig, many have stressed its importance. This is no doubt why the sciences, whether social or exact, so frequently resort to simplifications.

Ariel Rubinstein’s fables

In the sciences, simplification is often achieved through the use of models. In economics, for example, where complexity cannot be tackled without simplification, models are ubiquitous, thanks in particular to ‘simplifying assumptions’ such as the assumption of rationality or of equal access to information. Although these models are often described as “simplistic” or “unrealistic”, economist Dani Rodrik points out that their simplicity is precisely what makes them so valuable. A model sheds light on a particular aspect of the real world by focusing on the essential elements and removing those that might complicate understanding.

Economist Ariel Rubinstein compares models to fables: set in a fantasy world, fables teach a lesson that can be applied to reality. Similarly, models provide keys to understanding the real world based on fictional, simplified situations. In the sciences, simplification is therefore essential.

However, a problem arises when the conceptual framework is oversimplified or far removed from reality. Simplification becomes counterproductive, losing the virtues that were initially its strength. There is a fine line between “simple” and “simplistic”.

Basic, simple

In geopolitics, the study of world conflicts has been the subject of several interpretations, one of the best-known being Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” theory. His theory was first presented in Foreign Affairs magazine in 1993. Three years later, the American professor expanded on his analysis in his book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Both in the US and internationally, among the general public and in academia, his book has had great success. In 1993, Samuel Huntington hypothesised that the world’s major conflicts would no longer be about ideologies – as was the case during the Cold War – but would be between countries of different “civilisations”. His entire theory is based on the assumption that there are 8 civilisations: Western, Confucian, Japanese, Islamic, Hindu, Slavic-Orthodox, Latin American, and African.

It is clear from the start that the civilisations are not classified according to the same criteria. The “Buddhist”, “Hindu” and “Orthodox” civilisations are defined by religious criteria. By contrast, the “African” civilisation is defined geographically. As for “the West”, it is described in terms of abstract values — freedom and law. From the outset, the construction of Samuel Huntington’s conceptual framework appears to be lacking in rigour.

This oversimplification extends to the way world conflicts are interpreted. He sees the First Gulf War as a clash between the Western and Islamic civilisations. Of course, the First Gulf War involved countries belonging to both these groups. Some Gulf populations even shared a feeling of aggression after the US intervention. Nevertheless, the conflict was initially between Iraq and Kuwait, two “Islamic civilisation” countries. The United States then intervened at the request of Saudi Arabia and with the support of the entire Arab League. Similarly, it is a little simplistic to allude to an alliance between the Islamic and Asian “civilisations” on the basis of an increase in Chinese arms exports to Pakistan. The US exports massive amounts of military equipment to Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Shouldn’t the “Islamic civilisation” then be an ally of the West rather than an “existential threat”?

The seismologists of the Clash

Moreover, in order to make the Clash of Civilizations the paradigm of global conflict, Huntington focuses on conflicts with very wide media coverage. However, there are other conflicts and it is worth asking whether they actually support Huntington’s theory. In this respect, quantitative studies can provide interesting insights through empirical tests. According to the statistical analysis performed by Professor Jonathan Fox, non-civilisational insurgencies by ethnic minority groups are almost twice as common as civilisational insurgencies of the same type. The same applies to state failures: the number of non-civilisational conflicts is about two to three times higher than that of civilisational conflicts. Although this gap has narrowed since the late 1990s, the figures still do not entirely support Huntington’s theory. As for the quantitative analysis of the causes of conflict using OLS tests, it shows that the “civilisation” variable is not a significant determinant, unlike separatism, foreign interference and political repression. Jonathan Fox’s study is therefore useful for testing the relevance of Huntington’s theory within a single country. However, it does not take into account interstate conflicts.

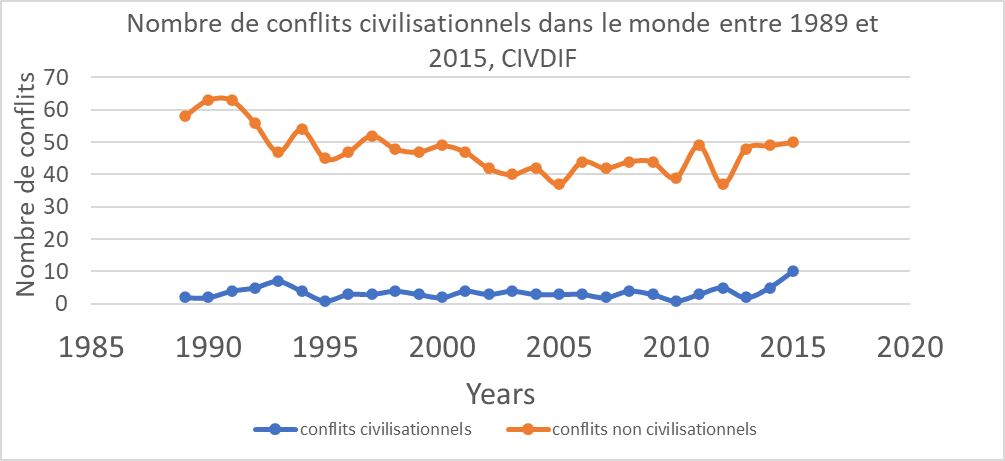

Professor Afa’anwi M. Che takes a more global perspective, by including all conflicts involving at least one state actor. When the geographically-bound conception and classification of major civilisations proposed by Huntington (civilisation difference or CIVDIF measure) is strictly applied, the results are revealing.

Blue: civilisational conflicts, Orange: non-civilisational conflicts

The significant difference between the two types of conflict (interstate and intrastate) is explained by the fact that this study considers civilisations as monolithic, uniform blocks. In this context, intrastate conflicts are almost automatically classified as non-civilisational, because the rebel or terrorist groups are geographically located in the same place as the government. In other words, this classification overlooks the cultural influence behind certain intrastate conflicts.

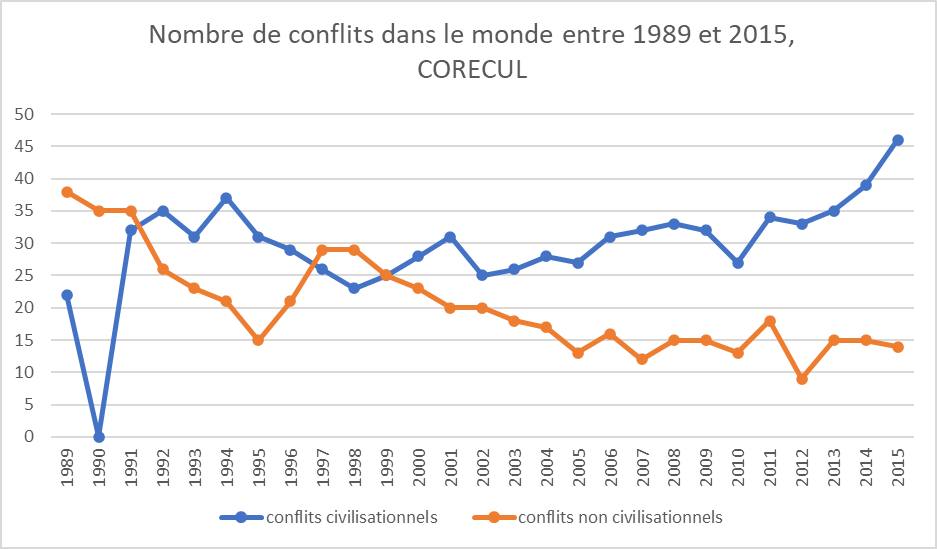

To correct this approach, Afa’anwi M. Che proposes an alternative classification based mainly on perceptions. A conflict becomes civilisational when a belligerent perceives itself as culturally different from its adversary.

Blue: civilisational conflicts, Orange: non-civilisational conflicts

With this new approach, the results are reversed and even tend to confirm Huntington’s theory. However, as the classification does not accurately reflect the theory, this method is open to criticism. For example, the governments of Algeria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Niger and Syria are perceived by jihadist groups as allies of the West, and are thus grouped with Western civilisation. Finally, Afa’anwi M. Che’s quantitative analysis quickly comes up against the difficulties of classifying civilisations.

Anarchy and civilisations

However, the main flaw in Huntington’s theory probably lies in its monocausal approach to conflicts. The professor raises the civilisational factor to the status of an absolute dogma, even though it is vague and imprecise, and he overlooks other determining variables such as political or economic interests.

Brian Pellerin draws on multiple levels of analysis to propose a conceptual framework that is both simple and capable of capturing the complexity of intrastate conflicts. In his view, a conflict can break out when a rebel group reaches or exceeds a certain level of motivation and capabilities. The motivation is broken down into a number of variables, spread across different levels of analysis.

A simple conceptual framework for understanding global conflict

In contrast to the limited approach of the Clash of Civilizations, this conceptual framework offers several levels of analysis for understanding the factors behind intrastate conflicts. The inspiration for this multiscalar approach comes from several authors, including Kenneth Waltz, Jack Levy, Greg Cashman and Joseph Nye, who have all demonstrated the complexity of conflicts, which cannot be reduced to a single factor.

The final straw

As Frédéric Munier, Director of the School of Geopolitics at SKEMA Business School, points out, political scientist Kenneth Waltz favours the systemic level of analysis. The latter asserts that the international system is “anarchic” in nature, because there exists no overarching authority above nation-states with an army, a police force (…) with a monopoly of power on Earth. In this anarchic system, any nation-state that increases its security is perceived as a potential threat, prompting the other states to arm themselves in return. This is what John H. Hertz calls “the security dilemma”. Next, the state level of analysis highlights more classic factors such as political instability or the “resource curse”. Finally, the individual level of analysis takes into account the greed of those in power and the frustration of populations following bad decisions by their leaders. This phenomenon, often described as “the final straw”, includes, for example, decisions to restrict rights and freedoms, to discriminate against certain sections of the population, or to ban certain legitimate political parties.

Read also: Why we go to war

By taking these different factors into account, this conceptual framework makes it possible to identify specific causes as well as complex interactions that would remain invisible in a monocausal approach. The multiscalar approach is also interdisciplinary: the systemic level of analysis draws on political science, the state level on economics, demography or geopolitics, and the individual level of analysis on social psychology. Thanks to this synergy between disciplines, the perspectives offered by different fields of research can be exploited. And to understand all aspects of a multipolar world, this level of complexity is more than welcome.