Given Saudi Arabia’s recent spectacular moves into sport and entertainment, you might think that their influence is nascent and temporary. But the network of Saudi investments is already very broad, and its ambitions are out of all proportion to those of its neighbours, Qatar and the Emirates.

So far this year, barely a week has gone by without there being news of yet another major development in Saudi Arabian sport. Recently, Saudi Pro League football clubs have been privatised, LIV Golf has agreed a merger with the PGA and DP Tours, and a host of players have agreed transfers to the country’s top football clubs.

Many observers have been shocked by the pace, reach, and unexpected nature of these developments. For instance, several of the world’s top football players have been signed by the kingdom’s clubs, including Karim Benzema at Al-Ittihad, Ruben Neves who turned down Barcelona for Al Hilal, and others such as Manchester City’s Bernardo Silva who is reportedly being pursued by Pro League clubs.

First of all, a Saudi revolution

After nearly two years of fractiousness, the Saudi Arabian Public Investment Fund’s (PIF) merger with the PGA and DP Tours stunned people across the world, even some of the sport’s leading players who claimed not to have known about it ahead of time. Despite their differences, a deal was struck that resulted in the PGA securing its financial future and PIF acquiring legitimacy in the eyes of the international sporting community.

As for the privatisation of its football clubs, it hardly constitutes a Thatcherite, free market revolution. Rather, it has prompted the notion of quango football whereby football clubs are independent of central government though still working for the state and pursuing state prescribed goals, laden with the kingdom’s assets as their sponsors, and with royal family members in key leadership positions.

All three developments are part of Saudi Arabian government plans that are intended to deliver on the country’s 2030 vision. Investing in the sport industry contributes to the country’s economic transformation programme, both in terms of generating revenues and creating jobs, but also in the way it promotes changes in attitudes towards enterprise and innovation.

Read also: Why Ronaldo’s move to Saudi Arabia increases the chances of an Afroeurasian World Cup

Sport is also intended to position the country as an event destination and a tourism hub. Evidence of the former is already extensive, with global motorsports, combat, and football competitions all having been staged in the kingdom. These have helped prompt infrastructural developments and the creation of civic amenities, which includes golf courses.

From Starbucks to Man United

Though some critics dismiss Saudi Arabia’s investments as sport washing, the view that such investments are only being undertaken for image and reputational purposes is limited though not without some merit. Becoming a prominent member of the global sporting community confers legitimacy upon a country, which impacts upon perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours towards that country. Government officials in Riyadh are aware of this.

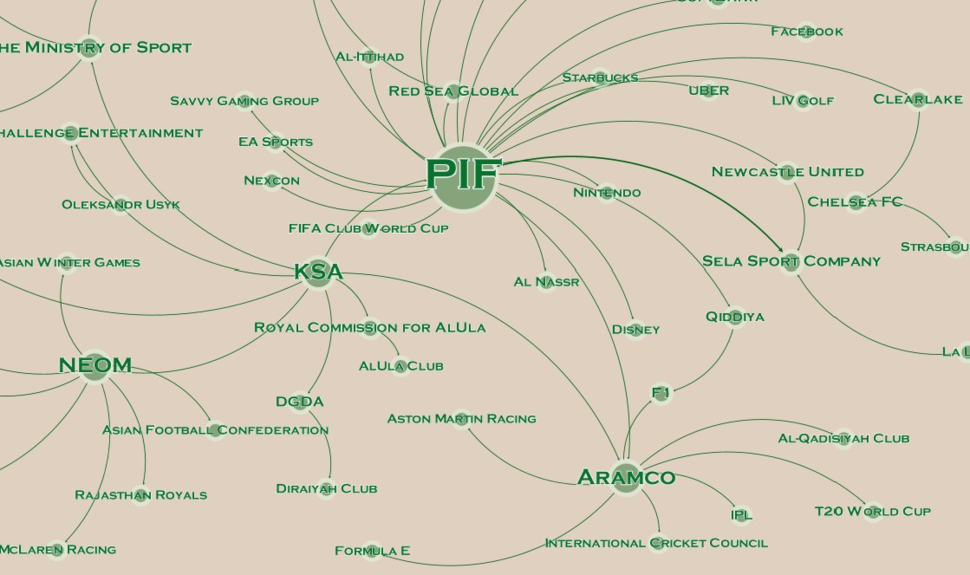

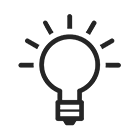

Given the pace and diversity of recent activity, allied to the intense scrutiny that Saudi Arabia is now subject to, we have visualised its sports investments. The circles represent economic entities, and a line represents a form of economic transaction which, when aggregated together, generate a market structure visualisation.

Click on the picture to enlarge

What is immediately evident is the range of different sports in which the country has rapidly established a presence, but also how prominent the state remains in driving related policy and strategy – indeed, node sizes in the visualisation are scaled according to the degree of centrality, that is how many economic transactions are coming in and out of that economic entity. Though as the recent developments in football privatisation serve to highlight, state entities other than central government are now being expected to play a role in sport.

Three types of investments

The investments being made are consistent with Saudi Arabia’s status as a rentier state; that is, there is an intention to derive revenues from assets located overseas. Furthermore, the allocation of football teams to entities such as Neom seems to be an example of rentier states’ preoccupation with allocative decision making at home. Yet there is evidence too in the visualisation of attempts to promote productive decision making (for instance, Sela is positioning itself as a profitable leisure and entertainment business).

Read also: Greenwashing or revolution, what is NEOM all about?

Otherwise, investments can be categorised in three ways; firstly, there have been investments in teams, including English Premier League football club Newcastle United. Nevertheless, the PIF’s recent disposal of its stake in the McLaren F1 team was somewhat surprising. Yet given the country’s engagement with motorsport, the move implies either a desire to focus its investments on the Aston Martin team (in which PIF also owns a stake) or perhaps that a new Saudi Arabian team might be established in the future.

Secondly, there is growing expenditure upon sport sponsorships, both domestically and internationally. The likes of Saudia (a state-owned airline) and Saudi Aramco are at the forefront of this, and we should expect the country’s new airline Riyadh Air – which is intended to rival Emirates Airline and Qatar Airways – to become involved in similar such programmes. Indeed, Qatar is likely serving as a benchmark for officials in Riyadh as the former’s ownership of French football club Paris Saint-Germain has witnessed the team’s shirts essentially becoming a global billboard for Qatari brands.

Thirdly, there has been a tranche of service, digital, and entertainment investments, of which the purchase of shares in Disney and Uber are examples. Once more, these are consistent with rentierism given that both are US headquartered businesses. They nevertheless serve other purposes, not least catering to the domestic needs of Saudi Arabia’s massively Gen Z skewed demography. Ownership stakes in EA Sports and Savvy validate this, esports are incredibly popular in the country and form part of its event hosting, tourism, and digital strategies.

This is a man’s world

Though the economic and political dimensions of the investment portfolio are undoubted, there are underpinning socio-cultural dimensions as well, notably utilising sport as a means through which to promote gender equality. Even so, there is a prevailing sense that football, fighting, and fast cars are at the core of what our visualisation has identified, which until 2018 were male dominated sports.

At the same time, the investments highlighted by this piece are redolent of other national development and sports strategies that we have already seen unfold, particularly in Qatar and Abu Dhabi. The differences between Saudi Arabia’s case and these others are the scale of ambition and the resources being ploughed into sport. Its ambitions are not simply regional or continental; instead, as we illustrate here, Riyadh’s sporting ambitions are bigger, bolder, and more bullish than perhaps we have ever seen before. There is a power shift in world sport, and it is heading East.