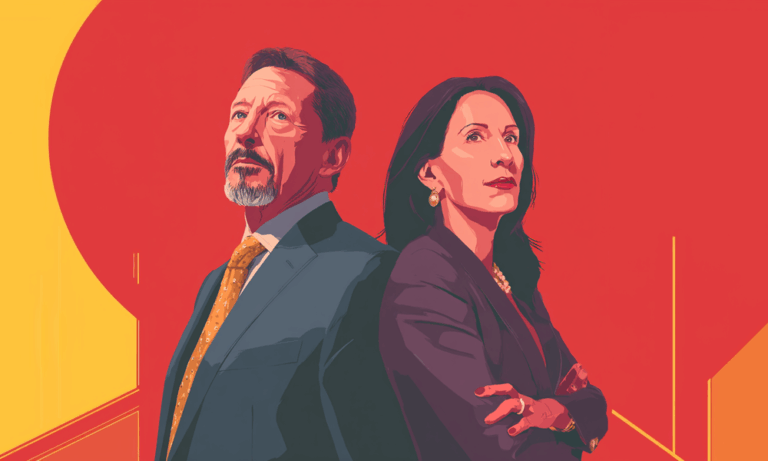

Lea Riccoboni x Carole Daniel : “Mindfulness allows us to make fairer choices in our daily lives.”

One is a professional triathlete who graduated from SKEMA Business School in 2018; the other is a lecturer and researcher at the same institution, and an amateur triathlete. Lea Riccoboni accepted the challenge of confiding in Carole Daniel, who specialises in the study of mindfulness, a meditative practice with powerful and surprising effects, such as improving performance, treating addictions, and even encouraging responsible consumption. Mindfulness is just as useful for elite athletes as it is for less sporty professionals.

Lea Riccoboni, have you ever practised mindfulness?

Lea Riccoboni: Not as such, but I do remember achieving a state of flow once, during a competition. It was in 2021, at the Ironman 70.3 World Championship in St George, Utah (USA). There was a kind of storm, a hurricane. It was so windy that the bikes started flying at the transition point; it was chaotic. When I got out of the water an hour later, it was chaos. And instead of cheering me on, my partner was shouting, “Lea, safety first!” It was in the desert; I could hear the sand hitting my transmission and the rain was falling heavily. But instead of being scared, I completely forgot about the weather and managed to ignore all the external elements. I couldn’t even see the landscape anymore. I was extremely focused. I had my head down and was giving it my all. I was so focused that I got a puncture on the last descent and didn’t even realise. I felt like I wasn’t even in my body. And that day I achieved my first world podium.

Carole Daniel, could Lea’s experience be likened to a state of mindfulness?

Carole Daniel: What Lea described was clearly a state of flow, which can also occur in the professional world. I have been studying this phenomenon for almost a decade as part of my research into mindfulness. It’s a state of total immersion in an activity, often triggered when the degree of difficulty is slightly higher than our current skill level. Some researchers, such as Steven Kotler (co-founder of the Flow Research Collective), estimate that this gap is optimal at around 4%. At this level, our attentional resources are fully mobilised.

Flow is about performance and achieving an objective. In contrast, mindfulness is based on the ability to be present in the here and now, without judgement and without seeking to achieve an outcome. It is a form of open attention, directed towards both the self and the environment. For example, practising mindfulness in a meeting means paying attention to what others are saying, your own reactions, and your response, despite any noise or distractions around you.

How is mindfulness practised?

CD: There are many ways to practise mindfulness. You can practise it while sitting, standing or even travelling on public transport. The key is to develop a regular routine, however brief. You can use breathing exercises, guided practices, or even compassionate meditations.

It’s a skill that can be developed through training, similar to training for a sport, except here you’re not working your muscles; you’re training your attention and emotional capacities. And, just like in sport, enjoyment plays a key role. If every session feels like a chore, you’re unlikely to stick with it for long. It’s important for each individual to find the right approach for them. Some athletes, for instance, use breathing exercises or music to regulate their stress levels or refocus before a race.

LR: That’s what my therapist recommends I do before a race or a training session. The aim is to achieve the right level of “excitement”. If you’re too euphoric, you’ll expend too much energy, and if you’re too calm, you won’t expend enough. I also do relaxation exercises to help with visualisation. I visualise my first transition, the moment when I’m going to overtake my rivals, and so on.

On that note, how do you mentally prepare for the transition between events in a triathlon? For example, how do you prepare for the transition from swimming to cycling, and from cycling to swimming?

LR: I have to be ultra-precise. This is all the more important at the professional level, where transitions have a huge impact. Towards the end of the swim, I visualise all the steps: putting on my helmet, taking off my wetsuit… There are real connections between mental preparation and physical efficiency.

CD: The transitions example is an interesting one. Mindfulness is often contrasted with “automatic mode”, or mind-wandering, where the mind operates on its own, undirected. However, in certain contexts, such as during transitions in triathlons, this automatic mode is necessary in order to act quickly and precisely. The key is to find the right balance: mindfulness enables you to refocus when your attention wanders, but it is not suitable for every moment of an event.

An ultra-runner recently told me that he uses mindfulness to stay connected to his sensations when he is low on energy, but lets his mind wander when he is in pain so as not to focus on it too much. This clearly illustrates that mindfulness is a tool to be used with discernment, depending on the situation and need.

Is practising mindfulness more effective if you also do some kind of sport?

CD: As far as I’m aware, few studies have looked specifically at the combined effects of mindfulness and regular exercise. However, the available results are promising, and it is reasonable to think that the two approaches can be mutually reinforcing.

What is fascinating is what neuroscience is teaching us: the brain, like muscles, has plasticity. We now know that our cognitive abilities are not fixed, even in adulthood. In his book The No-Nonsense Meditation Book, the neurologist Steven Laureys demonstrates, through the study of Matthieu Ricard, a Buddhist monk, that meditation can profoundly alter neuronal connections. So, you can be an athlete at the cognitive level and take up this “sport” at any age. This gives us great hope for treating depression, stress and certain injuries.

More and more athletes are speaking openly about burnout or depression during or after their careers. Could the practice of mindfulness be a solution to this phenomenon?

CD: Mindfulness is now one of the most widely studied tools for preventing and treating depression. The MBSR (Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction) protocol, developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn, was originally designed for patients suffering from chronic pain and stress. A therapeutic version (MBCT) was subsequently developed for people with depression.

Endurance athletes, such as triathletes, can be prone to burnout and performance addiction. Mindfulness can help break these addictive patterns. In fact, I published an article which shows that mindfulness can be particularly effective for people who are overly committed to their work — what we sometimes call “workaholics”.

LR: What I’ve heard most about is the post-marathon blues. This has never happened to me, because I plan my races over the medium to long term, so I always have one goal after another. But I can imagine that intensive training could frustrate some people rather than bring them enjoyment. Recently, I listened to a podcast about Strava and its potentially harmful effects: comparing your performance to that of others can become toxic.

Can mindfulness also help to recover more quickly from failure?

CD: Yes… Roger Federer comes to mind. He has won thousands of matches, yet in an address at Dartmouth College he revealed that he had actually won barely more than half of the points he had played. Maybe 53 or 54%. What made the difference was his ability to refocus his attention on every point. When he lost a point, he mentally “checks it off” and fully committed to the next one. This ability to “check things off” is something that can be learned through mindfulness. The ability to focus on what’s in front of us, here and now, not on what’s already happened.

LR: Recently, in Pucón, Chile, I experienced my first major disappointment. Up until then, I had always achieved my objectives, but on this occasion, with the excitement of the race, I realised that I hadn’t rested and I arrived tired at the starting line. My performance deteriorated throughout the race and, in the end, it was an hour and a half of suffering. I’d never had such dark thoughts. I thought I was going to give up; that I was going to end up walking to the finish line. I was very hard on myself and very critical of my performance. Afterwards, I analysed what had happened in detail and changed the way I prepared. These days, in a race week, you can bug me until Wednesday, but after that I refocus on myself. It’s very important to be able to quickly visualise something else, to be able to say: “I did that, I’ve learnt this from it, and these are the mistakes I won’t make again”.

Mindfulness can also have surprising effects on our lifestyle. Carole, you have conducted several studies investigating the connections between mindfulness practice and responsible consumption…

CD: That’s right. As I explained earlier, mindfulness is the opposite of the brain’s automatic functioning. Our consumerist lifestyles consist in giving in to our impulses without thinking. I see an item in a supermarket and put it in my trolley because I like the packaging, or because as I’m going down that aisle I’m hungry and I want sugar, so I buy the box of chocolate. Mindfulness introduces a brief pause between the stimulus and the response: in that moment I can ask myself if I really need the product, where it comes from, and how it was made. Mindfulness originates from the Buddhist tradition. It’s a way of reconnecting with the self, with nature, and with making better choices in your daily life.

LR: As a professional triathlete, this really resonates with me. I try to eat as simply and healthily as possible. My body is already under so much stress from sport that I look for simple foods that are the easiest to digest. I’m careful about everything I eat and make sure it’s as unprocessed as possible. I only buy vegetables from the market because they contain more microbes and that strengthens my immune system. I’ve developed an awareness of what I put into my body — it’s like a machine, and I control the fuel I put into it very carefully.

CD: The link with mindfulness is what is sometimes called mindful eating. As Lea said, it’s about listening to your body’s cues and choosing food based on your actual needs. It’s the opposite of wolfing down the first thing you can get your hands on, and of all forms of compulsive consumption.