Global warming is an established reality whose effects, which are now tangible for everyone, are potentially harmful for the planet. Yet, it can also bring with it unexpected opportunities. This is the case for Russia, where new trade routes and resource-rich spaces are now opening up.

Modern-day globalization is sometimes described as a “maritimization of the economy”. Indeed, it is estimated that 90% of goods traded globally (in tonnage terms) are now seaborne, transported across the oceans aboard tankers, bulk carriers and container ships. To get an idea of the sheer scale, the ourworldindata website provides real-time tracking of the world’s maritime traffic.

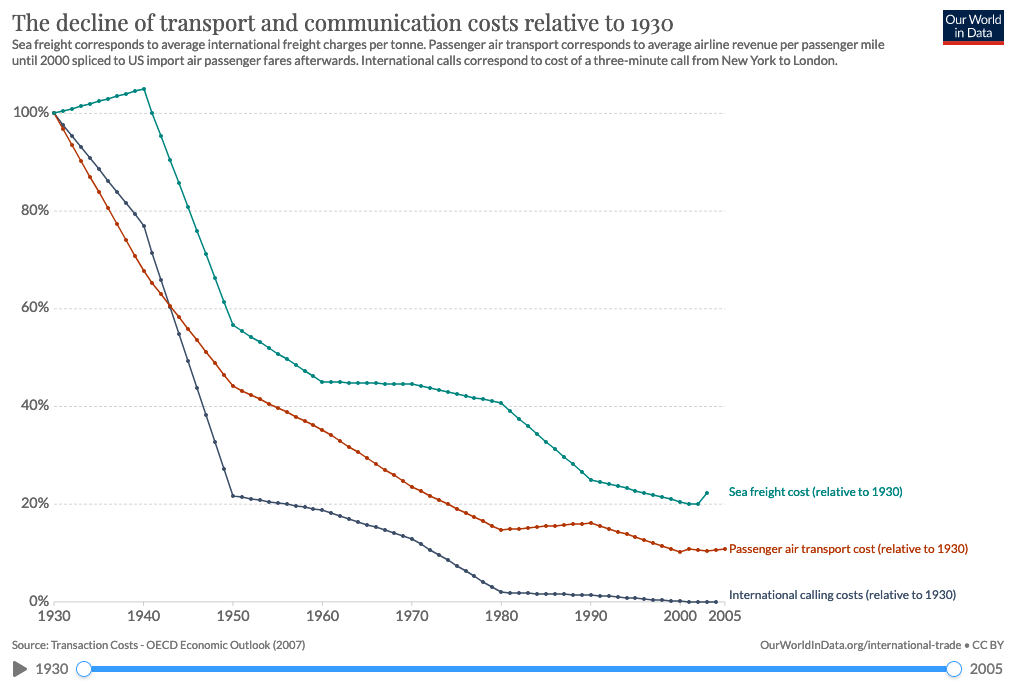

A century ago, all other things being equal, our world had experienced a similar phenomenon. The historian Suzanne Berger called it “the first globalization”. That period was marked by a vast movement towards trade openness, particularly among the European economies at the time, in which the seas and oceans played a fundamental role. In fact, it is within this context that the transcontinental canals were constructed. The Suez (1867) and Panama (1914) canals, to name but two, made it possible to connect seas or oceans and, in doing so, drastically reduced ships’ travelling time. If we add constant increases in ship tonnage to this and, since the 1960s, the rise in transport via container ships, it is no wonder that the price of sea freight has fallen so dramatically as to now make this the preferred means of transporting goods.

Economic theory establishes a link between this decline in the cost of transport and the increase in international trade, through so-called “gravity” models”. According to these models, the bilateral trade volume between two trading partners is proportional to their respective economic sizes and inversely proportional to the physical, institutional and cultural distance that separates them. More specifically, it is estimated that a two-fold increase in distance at sea leads to a 15% drop in trade volume.

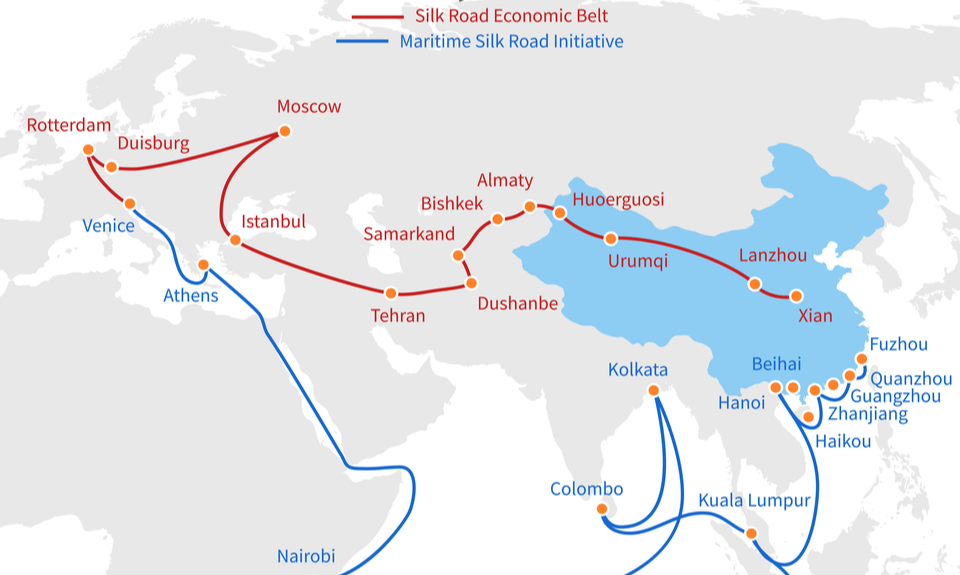

Now, in the early 21st century, the question of shipping routes is once again in the spotlight. The “new Silk Roads” initiated by Beijing in 2013, now called the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), comprise an important shipping route connecting Asia, Africa and Europe via the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. After the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages, the Atlantic Ocean in the modern era and the Pacific Ocean in the late 20th century, it is now the Indo-Pacific that is becoming the world’s busiest maritime space. This shift in trade is creating geopolitical rivalries in a space where the Chinese, Indian and American navies are present. And actually, as a sign of the times, in 2018 Washington merged its military commands in the Pacific and the Indian Ocean to create a unified command named USINDOPACOM (“United States Indo-Pacific Command”).

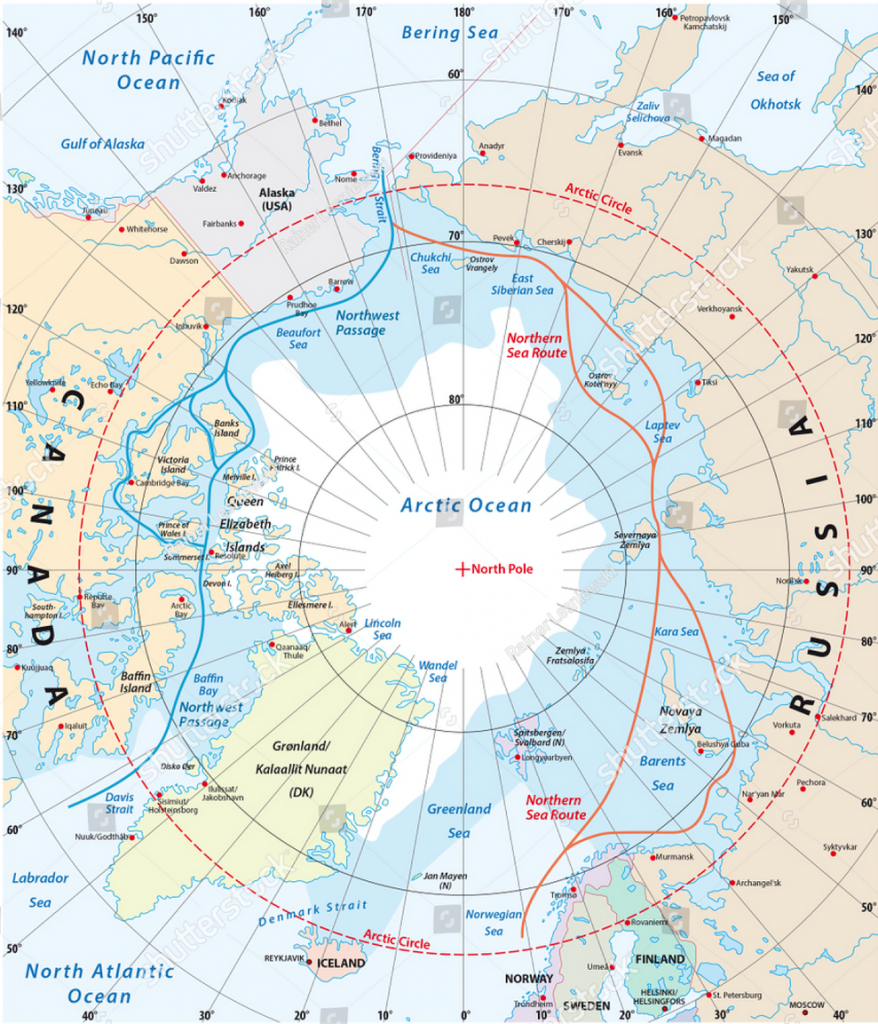

But there is one lesser-known route that is nevertheless attracting growing interest: “the northern route”. This maritime route, which goes through the Arctic, connects the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. It comprises two shipping routes: the Northwest Passage, which runs along the coast of Canada and, more importantly, the Northern Sea Route, which is shorter and more passable long term. That is why today the latter is of particular interest not only to Russia, which borders the Arctic Ocean, but also to China. It was first conquered in the 19th century by a Finnish explorer, and at the time of the Soviet Union port infrastructures were developed along it. The problem is that, until recently, the icy Arctic Ocean was impassable for a good part of the year due to the frozen waters. However, according to scientific estimates, global warming could make this route accessible for 65 to 75 days per year by 2080, versus 45 in the 1980s and around 55 today. In this region, the temperatures over the last few summers have been six degrees higher than those in the 1980-2010 period. This is resulting in a spectacular reduction in sea ice cover in September, a phenomenon not seen in nearly 1,000 years.

For some countries, the increasing access to this passage is a boon in more ways than one. First, from an economic and commercial standpoint, it would reduce the transit time between Shanghai and Rotterdam by 40%, and this in spite of the difficulties in navigating through the glaciers. Note however that the impact on traded volume would be small: it has been determined that for China, for example, there would only be a 0.9% rise in exports at the most. But there are other advantages to consider. Indeed, the rise in temperatures in that area would stimulate an increase in fish stocks such as mackerels and haddocks. With glacier recession would come the possibility of exploiting hydrocarbon and ore deposits. And finally, this passage is geopolitically safer as less subject to piracy than routes running through the Strait of Malacca, the Gulf of Aden or the Gulf of Guinea.

These many advantages explain why Russia has made northern Siberia a new pioneering front and is developing its ports there. The region is already exporting 80% of Russia’s natural gas, but also 90% of its nickel and cobalt… While it is difficult to evaluate just how much oil there is left to exploit, Rosneft estimates that there could be nearly as much as in Saudi Arabia. Incidentally, in 2017 Moscow inaugurated a mega liquefied natural gas centre in Yamal, foreshadowing other facilities of the same type. But Beijing will not be left behind: in 2018, China integrated the northern route into its vast Silk Roads project under the name “Polar Silk Road (PSR)”.

Here we are faced with a series of striking dilemmas that make our times so unique. The first concerns the interconnection between global scale and national scale. Global warming affects the entire planet, but in different ways. For Moscow, presently, it especially represents an economic opportunity. In these conditions, how is it possible to consider a global policy for addressing global warming? The second dilemma stems from the interconnection between the sectors affected by the warming and the ecological balances: while Russia may profit in the future from the maritime trade, fishing, and resource exploitation made possible by the rise in temperatures, these same climate conditions are also causing permafrost thaw in Siberia that could have terrible environmental consequences as large quantities of carbon or of hibernating microbes are released into the atmosphere. Thus, the Russian Silk Road illustrates how extremely difficult it is to take global political action to protect the environment when a phenomenon creates winners and losers that are not in the spheres and when the benefits and costs do not follow the same timeline.

To solve these dilemmas, it seems increasingly important to adopt a holistic approach in which economic short-termism is moderated by sustainable development goals. It is no longer scaremongering to consider that, in spite of the opportunities it can create for certain countries, climate change can threaten the survival of a portion of the human race.