As the covid-19 public health crisis has bitten, drastically reducing production and trade and therefore revenue distribution, economies’ financing requirements have soared.

Given the high economic and social costs of the pandemic and the need for an urgent response, the public and private sectors have progressively turned to new sources of financing, and in particular social bonds. These are a form of sustainable market finance which also include a social dimension.

The crisis has significantly accelerated the development of this nascent market, especially in Africa and emerging countries. According to the global fixed-income securities platform Cbonds, issuance of green, sustainable and social bonds is up 23% compared to 2019, and reached a total of US$84bn between January and April 2020.

The social bonds market’s record performance raises the question of how financing methods are changing, and how the notion of sustainable financing is becoming central to financial markets.

Social bonds are a good fit for a crisis

Social bonds are financial instruments issued on the bond markets by governments and businesses as a way of borrowing funds to finance actions such as access-to-education, -healthcare or -employment projects, in particular for disadvantaged groups.

The capital raised is used exclusively to finance or refinance, in whole or in part, new and/or current social projects. It must comply with the principles of socially responsible investing (SRI).

The main advantage of social bonds is that they allow organisations to finance high-social-impact projects at relatively low cost. Social bonds are often issued at low, or even capped, rates. Consequently, it is difficult for investors to speculate on the secondary markets.

The other advantage lies in the fact that bonds are often issued by private placement (meaning that the issue is only open to a limited number of investors), eliminating any opportunity to speculate on the issuers’ debt.

Social bonds are a lever by which private- and public-sector organisations can run or promote powerful social-impact projects.

As well as socially responsible investors, there are now private and public lenders on the capital markets investing specifically in social bonds (asset managers and investment funds, central and commercial banks, pension funds, insurers, etc.). This wider investor base offers governments and businesses opportunities to finance their social projects.

Over the last half-century, various forms of sustainable finance have been created across the world to minister to the excluded and the destitute in the face of financial crises and economic shocks. The most noteworthy have been:

- tontines (collective investment or pooled purchase of a property or other asset) and solidarity-based financing (savings invested in solidarity-based financial products): economic cooperation in Africa, Asia and France (Caisse solidaire, Association pour le droit à l’initiative économique);

- savings and lending schemes with the creation of Grameen Bank in Bangladesh in 1983, for example;

- in the 1970s, microcredit and microfinance with community banks (village banks) and microfinance institutions (MFIs) to help people excluded from the traditional banking system to access financial services;

- in the 1980s-1990s, ethical financing, which considers extra-financial criteria in investment and portfolio management decisions and favours investments in the “green and virtuous” economy that upholds human dignity;

- closer to home, Islamic finance, a system specifically provided for under French tax law since 2008. It covers all financial transactions and products that adhere to sharia law, which in particular forbids interest payments, uncertainty and speculation.

But sustainable finance is still mainly about community actions to support small-scale projects and specific individuals. In theory, it therefore appears to have limited compatibility with the urgent and specific financing needed to manage the public health crisis and its impacts, given that the pandemic has forced governments and businesses to borrow massively on both local and international bond markets to cover their soaring costs.

Integrating sustainability on a large scale

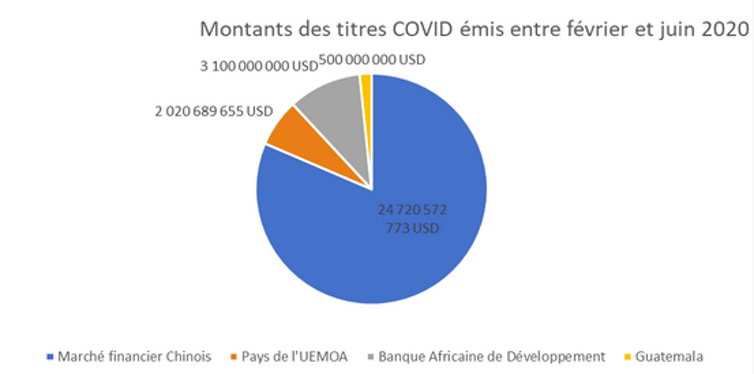

Between February and May 2020, local issues of [covid-19 securities] by Chinese businesses and banks listed on Cbonds (http://cbonds.com/) totalled US$24bn, set to mature in between three and 18 months.

On the international markets, Guatemala, a developing country, issued covid-19 bonds to the value of US$500m with a maturity date of 12 years.

In Africa, the African Development Bank raised US$3bn with a three-year maturity to help African countries finance their responses to covid-19.

The World Bank secured US$8bn in the form of a sustainable development bond to support developing countries’ efforts to reinforce their healthcare systems.

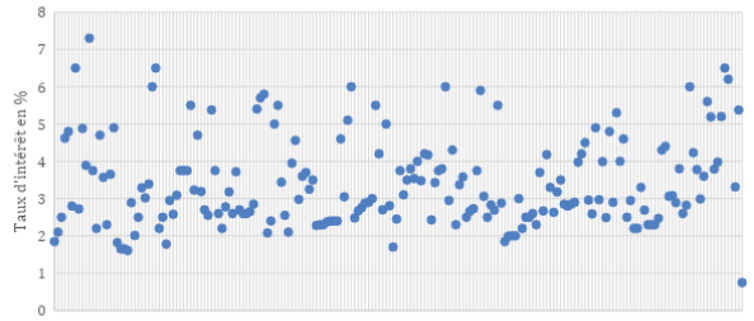

Between February and March 2020, interest rates varied between 0.75% and 7.3% despite the tight financial markets.

In the longer term, it is reasonable to imagine that the covid-19 crisis will alter the standard paradigm of finance. More sustainable and socially responsible finance could cushion the blows of future crises.

Although sustainable finance takes many different forms, the covid-19 crisis has moved it from an intermediary-operated model working through banks and microfinance institutions to a market model functioning via instruments such as social bonds.

This article was originally published on The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/social-bonds-changement-dechelle-pour-une-finance-durable-de-marche-141403