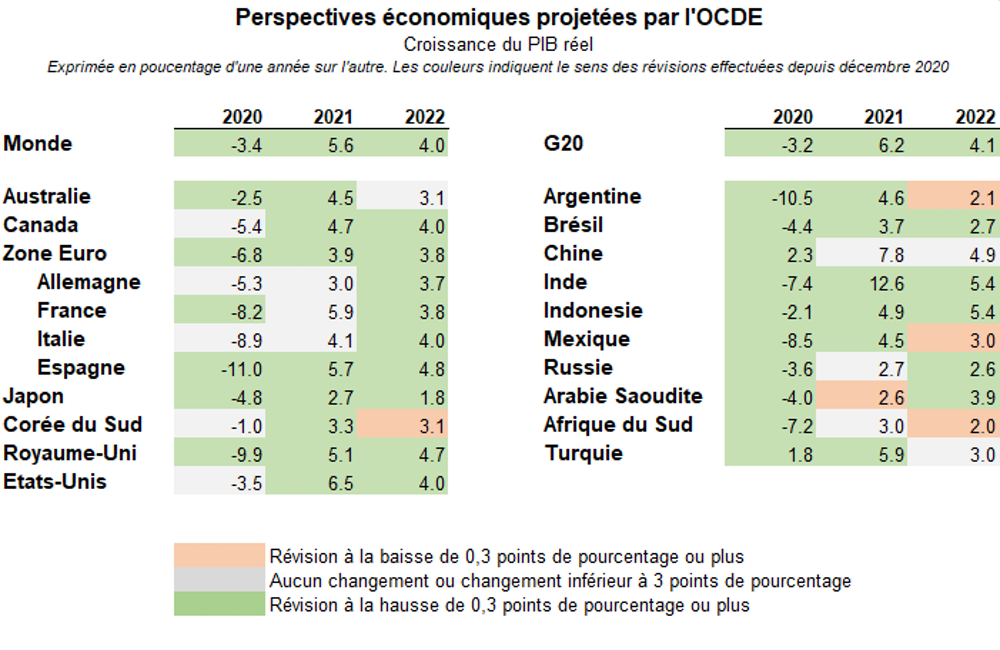

The American economic policy response to the Covid-19 recession was strong, aiming at limiting the drop in economic activity. The US economy shrank by just 3.5% in 2020, compared to 6.8% in the euro zone and 9.9% in the UK.

The American Federal Reserve (Fed) immediately intervened with a set of measures to ease monetary policy, lowering the federal funds rate to what it considered to be its effective floor (0%-0.25%) and developing unconventional responses such as buying securities on the markets and helping banks to supply liquidity to businesses.

Nevertheless, the most spectacular reaction was seen in spending policy. After a $900bn package approved in late December 2020, in March 2021 the Biden administration launched a second stimulus worth $1,900 billion, mainly to support households and increase public spending at federal and state level. In total, the budgetary stimulus amounted to 13% of GDP.

Shortly afterwards, President Biden announced an investment plan aiming to boost economic growth, together with a plan for families and education. The US seemed to be experiencing another “Roosevelt moment”.

Looking at the effects of such an enormous stimulus on the US economy, economists asked whether the economy could be in danger of overheating. They also began to question the global consequences of these two plans.

The consumer of last resort

Current estimates set American GDP growth for the first quarter of 2021 at 1.6%, and the IMF’s growth forecast for the full year is 6.4%. Of this growth, about three percentage points are considered to be a result of the Biden plan.

As regards prices, inflation spiked in April (up 4.2%), largely due to base effects (meaning that this growth is calculated compared to a lower base than usual – a year earlier, in April 2020, the Covid crisis was at its height and inflation was just 0.3%) and to upward pressure on energy prices (oil prices have risen by almost 50% in a year). Nevertheless, inflation expectations remain so far well anchored, suggesting only a short-term temporary impact.

Overall, a positive effect on GDP and prices following a fiscal stimulus is an expected result from the empirical literature. But it is also important to look beyond American borders to the international consequences of this policy, especially as the US is generally seen as the world economy’s consumer of last resort.

Despite the Trump administration’s attempts to reshore production and initiate trade wars, the American economy relies to a significant extent on imports, especially for goods. In 2020, the US trade deficit was $679 billion, equivalent to 3.2% of GDP and higher than in 2019 (2.8% of GDP).

According to the OECD, the Biden Plan accounts for about 1 percentage point of the 5.6% growth achieved by the world economy in 2021.

Consequently, when the American government launches a budget stimulus, it creates “import leakage” to the benefit of the world economy as a whole, and in particular those countries that are major exporters to the US and therefore profit from the increase in American consumption. In its latest economic outlook report, the OECD has, based on a macro-economic model, revised its projection for 2021 global GDP growth up more than 1 percentage point to 5.6%, mainly due to the Biden’s plan

Unsurprisingly, Canada and Mexico have the most to gain from this stimulus with production increases forecast at 0.5 to 1 percentage points in 2021, while the euro zone and China can expect to see increases of 0.25 to 0.5 points.

Increase in long-term interest rates

In the past, we have generally seen an increase in the Fed’s policy interest rate following a budget stimulus, as a way of curbing inflation. This in turn causes a rise in longer-term rates, and in particular the yields of the ten-year government bonds through which the US finances its debt.

This time, the nominal US ten-year interest rate increased by 70 base points (hundredths of a per cent) between January and April 2021, before falling back slightly to settle at around 1.6% in mid-May.

However, this situation does not appear to be caused by expectations of future increase in interest rates, as the Fed has stressed several times that it intends to continue pursuing its low interest-rate policy for still some time. In particular, according to the median projection of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the policy interest rate is expected to remain at around 0.1% until 2023.

Additionally, the Fed has changed its monetary policy strategy in August 2020, as explained in one of our recent papers. The current target is “to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time”. As price rises have come in below this target recently, the Fed will be prepared to tolerate a rise of more than 2% for a certain period. Consequently, unless there is a strong surge in inflation that pushes the long-term forecasts out of line, the Fed is unlikely to increase its policy rate in the medium term.

So what is the explanation? According to recent work by the IMF, two factors could be behind the rise in long-term US interest rates since January 2021.

Firstly, the markets expect to see inflation rise in the medium-term, fuelled by the prospect of growth in the US economy, higher prices internationally (raw materials, transport, etc.), bottlenecks in certain sectors that are suffering labour shortages and the Fed’s accommodative monetary policy stance, although the long-term forecasts have not changed. Secondly, the markets are requiring a high real risk premium in the long term (of around 70 base points). This reflects the strong uncertainty surrounding the economic, budgetary and monetary situation over the coming decade.

US federal bond issues are known to influence all securities across the international markets. Consequently, by contagion, since the start of 2021 we have seen an increase in the long-term interest rates across the globe, in particular the euro area and emerging countries.

In addition, a rise in long-term American interest rates tends to adversely affect certain emerging countries that borrow on the foreign markets because it means they face tighter borrowing conditions.

Dollar rebound

Most economic theories expect real exchange rates to rise following an increase in government spending, although this is not generally confirmed by empirical literature. Research attests that the results generally depend on the characteristics of the country in question such as the level of development or the exchange rate regime (fixed or floating).

In a recent paper on the American economy, that we wrote with two researchers from the Bank of Italy, we used military spending as an instrumental variable to identify the causal link between increased government spending and its economic effects. We demonstrated that, following a budgetary stimulus, the real dollar exchange rate appreciates with respect to the currencies of its main trading partners.

However, during the Covid-19 recession, the effective real dollar exchange rate fell by almost 10% due to concerns over the way the Trump administration was handling the public-health crisis. It picked up again by 2% between January and March 2021. Although exchange rates remain one of the most difficult economic variables to predict, our study suggests that we can expect to see a rebound in the effective real dollar exchange rate following the implementation of the Biden’s plan.

This would increase the trade deficit even further by making American exports more expensive. Additionally, this exchange rate rise could cause problems for emerging countries holding high levels of dollar-denominated debt.

Where one goes, the rest will soon follow?

There are other ways a spending policy shock can have international repercussions, too. Several papers have demonstrated the US’s capacity to generate uncertainty on a global level.

Consequently, the implementation of the Biden plan and the positive effects it is expected to have on growth will help to reduce short-term economic policy uncertainty in numerous countries. Conversely, higher government borrowing has increased long-term economic uncertainty, which could potentially have in turn international implications.

The transmission mechanism described in Keynesian theory could also come into play. The fact that the world’s biggest economy has put in place a large-scale public spending plan could well encourage other countries or currency areas to significantly relax their public spending constraints as a response to this unprecedented public health shock.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article (french version).