We all know about the David against Goliath story and the result of their battle. When applied to startups and large firms, the asymmetry of the situation of the stakeholders usually ends up the other way around. This asymmetry is even more an issue in situations of crisis such as the one we face with the COVID19. The former may see it as an opportunity to redistribute cards. The latter may use it to reinforce existing positions. In fact, concerning business relationships, neither scenario should prevail, as there is no lasting business partnership that is not perceived as beneficial for both parties. The key question is, for the sake of each party’s interest, how can an asymmetric partnership between a startup and a large firm be made to work?

Agile like David, strong like Goliath? Not that simple

Raising the issue of asymmetry is the first step towards obtaining the answer. How asymmetric is the situation between a small, fast-growing young firm and a large, incumbent, well-established company? From the resources perspective, startups lack the organizational slack of financial and human assets that large firms usually possess. This cushion of actual or potential resources allows large firms to adapt to internal or external pressures for adjustment, whereas startups are constrained by the need to carefully allocating the right resources to the right project. This may generate power imbalance in the negotiation as the startup may become locked in the partnership, and consequently, prevented from having discussions with competitors of the large firm.

Startups also use their inherent agility to capture market or product opportunities and their planning horizon usually does not exceed a few months. They may also underestimate the gap between a prototype and a fully supported solution, be it a product or a service. This may lead to a poor appreciation of the time and cost required to move between the two. From a strategic posture perspective, startups generally practice (and are pushed in this direction by many non-practitioner scholars) “strategy along the way” and forget that strategic planning does not mean rigidity but rather aligning the use of resources with business objectives in the appropriate business model. From an organizational standpoint, startups favor ad hoc processes and staff versatility in decision making and action . Wearing several hats at the same time may make it difficult for startups’ leaders to find the right counterparts in the large firm where there is a clear separation between line and staff roles.

Conversely, large firms follow explicit strategies, have well-established market positions, and benefit from efficient operational routines. However, this may lead to market myopia and reduce innovation effectiveness – the well-known innovator’s dilemma described by Clayton Christensen[i]. Moreover, the separation between line and staff role hampers the creation of new knowledge via cross-fertilization and makes it difficult to see the “big picture” of the innovation scope when working with a startup, thus underestimating the real value of the partnership. This inability or unwillingness to open the scope of their product-market domain may also lead large firms towards an ex-ante reluctance to even consider the innovation brought by the startup. By doing so, they add-up the “not invented here” syndrome to the innovator’s dilemma.

Having said this, and considering the embeddedness of these asymmetries in each partner, how can asymmetric partnerships result in shared success? The answer may lie in a shared cascading process stemming from strategic intent to business modelling and partnership implementation.

A mouse may be of service to a lion … and vice versa

First, the likelihood of developing a win-win partnership increases significantly if it is supported by “committed advocates” within the large firm that will facilitate decision-making and working processes with the startup. These commonly respected individuals play a central role in building trust and developing effective channels of communication between the partners. They create a bridge between both firms by fostering complementarities and reducing the perception of asymmetries. As “advocate” of the startup within the large firm, they facilitate the sharing of information between parties regarding strategic objectives, organizational routines and processes, and stimulate tradeoffs about the operational plan of the project.

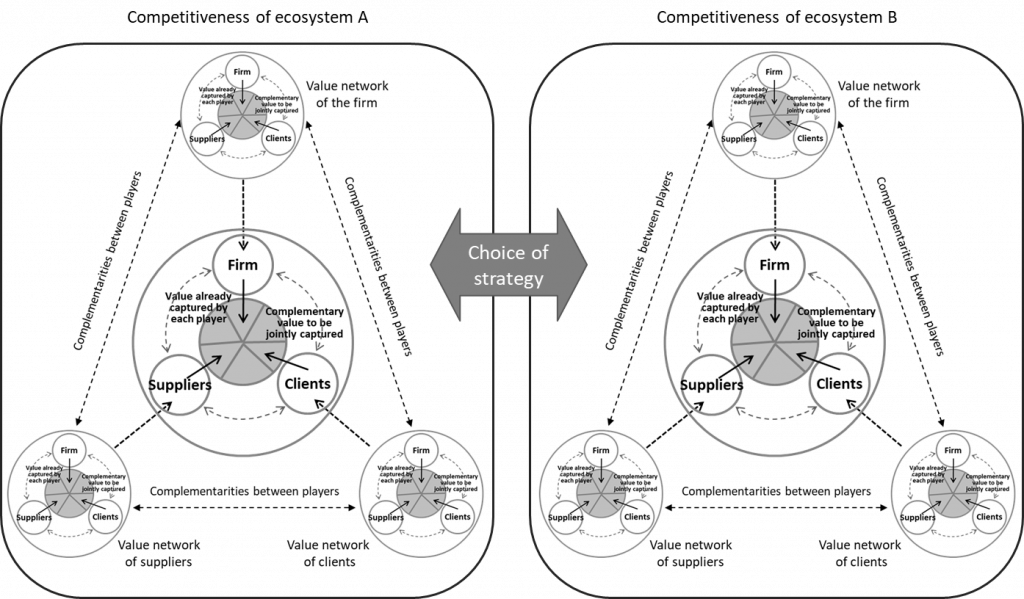

Second, both parties should reconsider their strategy of competitive positioning characterized by unilateral supplier-client relationships for a strategy of ecosystem where multilateral relationships between all stakeholders prevail. In other words, startups should consider their partners – clients, suppliers, and facilitators – according to their own individual potential interest in the startup’s success. From this standpoint, a large firm can be a valuable supplier if it sees the startup as a Trojan Horse to explore new market opportunities. With this opportunity-cost perspective, it is in its own interest to contribute to the success of the startup by lowering its negotiation power. Conversely, a startup can develop a win-win partnership with a large client when the latter lacks a “component” in its value proposition that can be supplied by the startup or when the startup’s value proposition leverages the one of the large firm. The key aspect here is that each party makes its own strategy explicit to the other before entering into negotiation.

From competitive strategies to strategies of ecosystems

Source : adapted from Chereau and Meschi, 2019. Le Conseil en Stratégie, Vuibert.

Based on these shared strategic intents, startups and large companies should think their strategy as an action plan to align with the players of the competitive ecosystem in which they wish to develop and secure their position[ii]. In practice, like the competitive strategy, the ecosystem strategy is built on a double external-internal analysis. On one hand is the external analysis of the inter-ecosystem competitiveness to evaluate the collective capacity of the actors of an ecosystem to create more value for the end customer than another ecosystem. On the other hand, is the analysis of the intra-ecosystem competitiveness to assess the complementarities between the players of the ecosystem and the overall consistency of their positioning.

To rebalance their relationships with large firms, startups should favor a business model that reflects their ecosystem strategy, thus, intrinsically mirroring the one of their chosen partners. Indeed, by designing an offer allowing large firms to foster their own value proposition, while cooperating with suppliers or facilitators willing to be part of this value network, startups may generate a virtuous cycle that will make asymmetries and power imbalance obsolete.

What if David and Goliath made common cause, eventually?

[i] Christensen C.M. (1997). ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma’, Harvard Business School Press

[ii] Adner R. (2016). ‘Ecosystem as structure : An actionable construct for strategy’, Journal of Management, 43(1)